return to homepage THE PRE-PICASSAN BROTHERHOOD

return to updates

by Laura Alport

Sometimes things still happen. I stood, watery drink in hand, outside the main circle of conversation at an unexceptional party in a nondescript house in a town not known for its art. Why? Why indeed, and very broadly. A sheet of noise reflecting from every surface—the too-close walls, the humming glasses, the enameled and polished things all about—hemmed me into myself, and I fell back behind my eyes, alert but ineffable. I may have swayed slightly, I don't know. Suddenly, impinging softly on one of my outer meridians, a strange voice. Someone nearby was quoting van Gogh. I heard through the tintinnabulation of lesser voices, "Better a little wisdom than a lot of energetic zeal." Do I yet dream? I slipped around the corner into a dim hallway—an ell of Hypnos, perhaps—and found myself directly behind two blondish eidola, seraphic bookends, in heated dispute with half a dozen others on the subject of modern art. One of them had raised the ghost of Vincent, supposedly one of the fathers of Modernism, to completely dismantle the modern theories of his antagonists. The listeners were dumbfounded. As intellectuals, they were clearly accustomed to browbeating anyone foolish enough to broach this subject. One of them began,

“But Foucault thought...."

He was immediately interrupted with, "What was it that Foucault painted, again?"

He answered, "Nothing that I know of, but...."

"Let's leave him out of it then."

My eyelids danced and my fingers trembled without volition. Somewhere a chorus mouthed a weird chantey. A few minutes later the two guys left, and I asked someone, "What just happened? Who were they?"

"The Pre-Picassan Brotherhood."

"No, really."

"Really. They think they're the saviors of art or something. Big deal."

My informant here was clearly a hostile witness. A fan of Duchamp or Damien Hirst. So I did my own work. Intrigued, I tracked down the "Brotherhood." Honestly, I expected to be disappointed. I usually am. In this age of gimmickry and technical shoddiness, one becomes jaded.

From the street the studio appears unimpressive. An old stone house in an unkempt yard draped by low-hanging trees and knee-high grass. But inside it is like a step back in time. The smell of turpentine and rabbitskin glue. Bags of rich red clay and muddy wooden tools. Fine linen canvases primed with white lead, or birch panels layered with chalk gesso. No interior latex here. No broken plastic dolls. No industrial gadgetry being rewelded or collaged. Nothing being quoted or hypertexted. No animal corpses or back issues of ARTnews. Not even a TV, not anywhere.

On the walls are oil paintings, watercolors, pastels, and charcoal drawings. Other works framed and unframed line the baseboards four and five deep. On every available horizontal surface sits a figure in clay or plaster or bronze. I have forgotten at times that art is still possible.

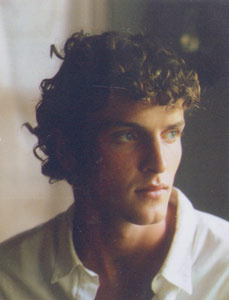

The Pre-Picassan Brotherhood is Miles Mathis and Van Nielsen. Everyone assumes at first they really are brothers, as I did, but they are unrelated. In fact, they are eleven years apart and from different states. Mr. Mathis is 36, a Texan. Mr. Nielsen is 25, and is from Colorado. But like fraternal twins they can alternate in conversation without missing a beat, one taking up where the other left off. I always get a bit dizzy talking to the Brotherhood.

The first thing one notices about the Brotherhood (after that hair) is that they seem—how should I say it?—unworldly. They appear to have just tunneled in from the 19th century. Your first reaction is to hold it against them, but it is not easy. They won't let you. Mr. Mathis was Phi Beta Kappa in philosophy before he became an artist. He has read everything. If you puncture his reticence, his natural quietude—with an equivocal remark about Warhol, say—you then begin to get an opinion for every subject and, what's better, a story for every opinion. One minute it is Praxiteles and his model Phryne in ancient Greece; the next it is Whistler suing the art critic Ruskin in Victorian England; the next it is how Rodin would have answered Pollock, or what Picasso should have told Gertrude Stein, or how Cellini would have dealt with the insolence of Clement Greenberg. In the world of Mr. Mathis, Nietzsche is always scolding Sartre, or Freud is psychoanalyzing Lacan, or Michelangelo is punching Arthur Danto (The Nation's current art critic] in the nose. Its great fun really, as long as he's not attacking your balloonman (Warhol fared rather poorly in our argument, I must say).

But it's also curious, in a way, all this talk. The work needs no justification. A great painting or sculpture requires no theoretical underpinning. But, as Mr. Mathis explains, he and Mr. Nielsen formed the Brotherhood expressly to "call the critics out." The artwork itself is not a response to anything; it is, as Mr. Nielsen says, "A drink for the Muse." But what they say and write about art is a response. The Brotherhood is of the opinion that artists have lost control of the definition of art, and that critics and curators and academics have redefined it to suit their own purposes. Before the 20th century, art was defined by artists. During the 20th century, art has been defined by non-artists. This is the central problem.

And so, in order to out-write the writers and out-talk the talkers, it is now necessary to "know the enemy." Mr. Mathis told me,

"What the 90's have shown me, after the [art] market crash in the late 80's, is that Modernism is so entrenched, in the big museums and universities, at the institutional level, that it is not going to fade away. A lot of realists think that all they have to do is work and wait. That's what the realists thought in the 40's. In the 60's. But Modernism butters a lot of peoples' bread. It will have to be defeated, from the top down. A lot of people, people with a lot of power in the art markets, cannot approach art emotionally. They must view it intellectually. Political science has co-opted art. Analysis has digested synthesis. What is needed is a return to patronage—a coalition between real artists and the huge pool of quite intelligent and insightful people who find no art in 'art moderne.' We must create a direct link between the artist and the public to bypass criticism. Art theory has become a fashion. But it is never fashionable to be wrong. The tide will turn when it is clear that our pool is deeper."

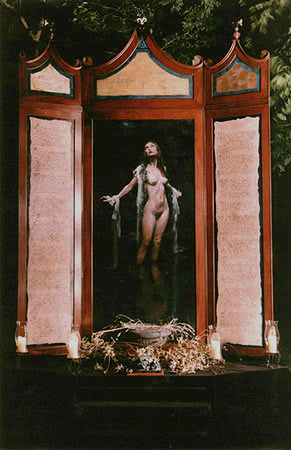

One of the "deepest pools" in the studio is a work by Mr. Mathis that he calls The Triptych Altarpiece of Harriet Westbrook Shelley.

Harriet Westbrook was the first wife of the great Romantic poet Percy Shelley, whom he left for Mary Godwin (she later wrote Frankenstein, remember). Harriet drowned herself in the river that flows through Hyde Park in London. The triptych consists of a central oil painting, eight feet high, flanked by two panels of poetry in script. The poem is (we are to believe) by Harriet, and in it she addresses the ghost of Percy. Percy drowned, too, in a boating accident, six years after Harriet. In the poem, the two drownings are connected; are no coincidence. The painting is of Harriet, rising from the water at midnight. There is also a sculpture of Harriet—a reclining bust—on the triptych's platform, among the candles. The gigantic mahogony frame, fifteen feet high in all, sports fishes and a seahorse above a rolling wave pattern at the top.

We have all been taught in our art history classes that the great subjects have been exhausted, that there is "nothing new under the sun." That epic or transcendent imagery is not relevant to our situation. The Brotherhood apparently missed that day.

Many of Mr. Mathis' other works are also nudes, although none of the others are as thematically ambitious. Still, a sadness or a melancholia permeates all his work. A little girl holding a ball. A young woman looking out a window into white light. A profile, half in shadow. Simple subjects, painted directly, unstylized, and yet somehow heartbreaking.

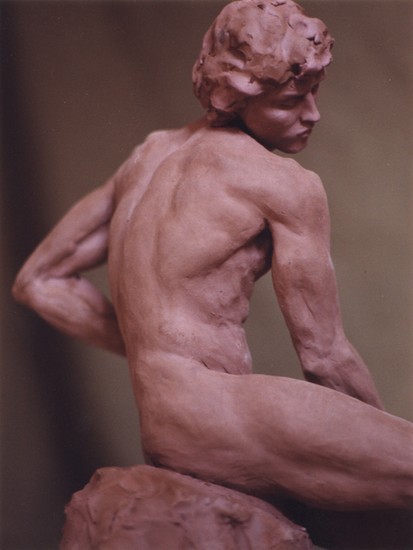

Mr. Nielsen's works are also highly emotional. Most of the sculpture in the house is Mr. Nielsen's. Concentrating on the nude male figure, he is obviously a student of Michelangelo. There is no break from nature, nothing of the existentialist, in these poses. The psychological calm of the Renaissance joins the physical tension of Rodin or Carpeaux, and yet these figures somehow avoid any direct derivation. One, a plaster "original" of a standing nude, depicts a long, straining body, arms and legs contraposto, topped by a serenely beautiful head—a head almost unaware of its torso's arch, its soul's ache.

Nearby is a halfsize bust of a young woman looking down, half smiling to herself, half brooding. I was reminded of one of Bernini's "speaking likenesses."

It is less refined than Bernini; but, perhaps because of the raw clay, it seemed even more alive. Another small figure, called by Mr. Nielsen Thanatos (the god of death), almost made me yearn for the grave. Death should not be so attractive. But one gets Mr. Nielsen's point. There is something uncanny, almost sinister, about such perfect beauty. It is hard to feel safe, at ease, in its presence—death or beauty—especially when it won't look at you.

"Why the 'Pre-Picassan Brotherhood'?" I asked the "brothers."

"Well, we wanted something memorable. And descriptive," answered Mr. Nielsen. "We both love Picasso's early work. The Old Guitarist. The Harlequins. But around 1905 he started listening to the critics—Roger Fry, Leo Stein—and it all went south. Picasso even admitted it. Then came Kandinsky and Duchamp and the rest: all the talk, the posing, the theorizing. Art as criticism. Art as politics. We wanted to get back to art as art. Art as creating something incredibly powerful or beautiful. We talk a lot—but, I mean with us, the work is primary. We don't talk about what our art means. We talk about why their theories are wrong."

"But aren't you concerned about the 'sexist' label?" I said. "All these female nudes, with no 'spin,' no clever, progressive message. And the 'brotherhood?' What's with that? You guys don't let girls in the club?"

Mr. Mathis fielded this one. "The Brotherhood is just us. Two guys. Is it now incorrect to call two guys a 'brotherhood'? As for the nudes, it is interesting that you only ask about the female nudes. The male nudes that we both do might equally be called 'objectified,' or whatever you mean. The point is that none of the figures, or the models, are treated as 'objects.' They are treated as subjects. Subjects for a work of art. They aren't just material bodies. They are invested with more importance than in daily life. Not less. They aren't 'used.' They are universalized. Just the opposite."

This answer, as unexpected as it was honest, somehow rang true to me. It sounded like something Rodin might have said about art. Or Degas. Straightforward, stripped of jargon, but with a blistering and beautiful acuity. It made me think:

As I drove home from the studio I looked out into the "real" world. I saw the hurried people zipping past—SUV's and cellphones—even in this un-metropolitan town. And I remembered my time in New York City. I hope the Brotherhood has some armor that is not only well-polished but seamless. And they may, I don't know. They will need it in the first years of the 21st century. Idealism doesn't travel that well anymore. It is one thing to remain pure in the relative isolation of the west, before the pressures of money and fame have really taken hold. It is another to translate that to the reality of the major art markets. I am not sure it can be done. But I hope it can. I for one am weary of the din of small explosions that is the trade of Deconstruction and Postmodernism. It is pointless to go on strafing barren ground, bombing the surface of the Moon. A true progressive must begin to rebuild at some point.