return to homepage Graydon Parrish When Graydon’s work was first unveiled I promised myself I wouldn’t make any public commentary on it. So much for that. Graydon is one of the few people in the world who I do not relish having as an enemy. Not because I am afraid of him or because he is such a close friend, but simply because I respect him. In fact, Graydon is not a close friend. Although we are both native Texans, and although we lived about a block from eachother in Massachusetts for four years, I have never met him or spoken to him in person. We have exchanged a few short emails and that is it. I like him, as far as one can tell from such things, but I don’t think a few emails makes a friendship, close or not. I am sharing these personal facts with my readers so that they may take this critique as an objective one. I don’t want anyone to think that what I am about to say is a defense of a bosom buddy. It is not. As you will see, it is basically another all-out assault on Modernism, and Graydon’s experiences after the unveiling—to the small extent I know them—are used simply as starting point for my commentary, not mainly upon him, but upon those around him in this minor circus.

Like the wolf, the commentators on the right have starved themselves into a corner. For them, Modernism is a dead-end, but, because they don’t want to be seen as completely “out of it,” they have accepted, consciously or unconsciously, important parts of the Modernist program. They don’t want to go forward with Modernism on its current tack, but they don’t want to go back. They want skill but they also want astounding relevance at all times, by the modern definition. And they will dismiss any realism that does not immediately trump all previous realism (as Modernism claimed to immediately trump all previous art). Hence the absurd comparisons to Raphael. They expect craft and novelty simultaneously. Despite knowing full well that craft in art just underwent a century of obsolescence, they judge new realism by higher standards than old realism. A technical mistake in Rembrandt or Chardin or Goya is easily overlooked, for instance; a similar mistake by a new realist is cause for full dismissal. Many are so keen to prove their knowledge and taste that they can be pleased by nothing. Others let the contradictions listed just above lead them into astonishing lapses, such as Hilton Kramer mistaking Odd Nerdrum’s art as earnest, or Robert Hughes doing the same with Lucian Freud [both Nerdrum and Freud gave the market what it wanted—weirdness—and they did so from a burning desire to succeed. Freud was much better at selling out to the in-crowd, but Nerdrum got it right at last.]

The greatest tragedy in all this may not be 911, and it certainly is not Graydon’s painting (in the sense that Mr. Panero called it a tragedy); the greatest long-term tragedy on display here is the bottoming out of art criticism. If I thought that this bottoming out was the final step toward extinction, I could embrace it fully; but it is nothing like that. I think it is clear that this bottoming out signals the final vulgarization of analysis: not its end, but its arrival at a permanent nadir—a culture-wide, equal-access morass.

Hughes and Kramer and Panero and all the rest of the confused critics, from top to bottom, don’t seem to have any idea what the river or road out of Bedlam looks like, so I will tell them. It looks like Graydon Parrish. He is not all the road, neither the whole width nor the whole length of it, and assuredly not the end of it: but he is on the road, making his honest way. How far along that road he will go, and how large a track he will make, is yet to be seen, but all on that road deserve a merry wave and a free AAA card. For, unlike those on the Modern road—which is unpaved, piled high with plastic litter (and which turns out to be a closed oval with turns banked the wrong way)—the road Graydon is on is paved, straight, and with plenty of room for widening. It will not take all traffic, but the pavement is pleasing to the best tires: here one can accelerate with no loss of tread, with just touch of the throttle.

return to updates

and the 911 Memorial

by Miles Mathis

As everyone knows who has read more than a couple of my papers, I don’t like politics or allegory in art. As some know who have combed my site carefully, I am also a 911 Truther—meaning, I strongly believe that everything that happened on 911 was planned and carried out by our own government. For these reasons, among others, there was no pleasing me with this 911 Memorial. Nothing that Graydon could have done would have pleased me artistically. If he had gone after the CIA and the neocons and the Pentagon like a Berserker, showing the crime in all its heinous detail, it might have pleased me politically, but it still would not have pleased me artistically. I don’t like to see art used that way. Art, in my opinion, is too good for that. Leave that to the papers, which were created for reportage.

However, none of that is really to the point in this case, which is why I haven’t had anything to say about the Memorial until now. Graydon was hired to paint this Memorial by someone who wanted a memorial, not an attack piece. They didn’t want a grand statement, a crusading documentary, or a hook for a revolution. They wanted a memorial painted by a talented realist, and they got that. I imagine they are pleased as punch. If they are not, then I imagine it is mostly their own fault for not being more specific about what they did want.

[Two things I do like, politically, and I will pop them in here. One, the crumpled up Constitution, for obvious reasons. Two, the title, The Cycle of Terror. I like that word “Cycle,” which has not been given enough attention. Think about it. Graydon may be doing a bit more here than most people know, more even than the annotation will admit to. Concerning other parts of the Memorial that may now seem a bit naïve to some, we must remember that Graydon began this painting soon after 911, when we were all a bit more naïve. The last five years has been a time of great change, politically. The Constitution was likely added to the painting at later stages, for example, and the title could wait till the end. So if some parts of this Memorial are more iconoclastic than other parts, it should not come as any surprise to us.]

No, what led me to write this is the asinine response to the 911 Memorial by the media. It is not anything that Graydon did that pissed me off, it was the writers once again. I have read critiques from all quarters, from the predictable slurs of the avant garde mouthpieces like the New York Times, to the nearly-as-predictable slurs of the rightist journals, such as The New Criterion. Not one of them has the slightest hint of a historical perspective. Reading them, you would think that this was the only painting that had ever been attempted in the history of the world, and that the history of the world began about ten minutes ago. Meaning, they are all perfectly willing to lash into the painting for any good or bad reason, but not willing to look around and compare it to all the other so-called art surrounding it for the last century. None of the critiques I have read have compared Graydon’s work to any pre-Modern works either, history paintings or allegories or political paintings or memorials, except in the most cursory way. They have implied, with no argument or direct comparison, that it doesn’t hold a candle to the great paintings of the past. But even if that were true (and I don’t think that it is) it would be horribly unfair. When Louise Bourgeois or Bruce Nauman unveils her or his latest little piece of faux-afflatus, we do not see the critics setting it next to The School of Athens or the Raft of the Meduse and pooh-poohing for pages. Graydon’s painting was just painted, and as a new painting it deserves some benefit of the doubt, some minor amount of empathy. That is to say, before it is looked at in competition with Apelles and Michelangelo and Tintoretto and David, it should be looked at as a contemporary artifact, a contemporary creation. It should be compared to the other art around it. If it is looked at in that way, it is immediately Olympian in comparison.

For instance, James Cooper of the Newington Cropsy Institute was quoted on NPR as saying that Graydon was not Raphael (which he pronounced like Raffy-L: isn’t that a rapper?). Yah, well, no one claimed he was, least of all Graydon. And I have some shocking news for you, Mr. Cooper, neither was Jasper Cropsy. Jasper couldn’t paint the figure at all, he was just another landscapist. Why is it, precisely, that you can promote Jasper and not Graydon? One suspects that it must have something to do with something besides this Raphael rubbish. [More on that suspicion below.] Greg Hedberg at Hirschl&Adler pretended he was too good for the new realists for a while, too, saying that he was “waiting for them to mature,” or something like that. Really infuriating, considering the “mature” things Mr. Hedberg was promoting before we came along. But Mr. Hedberg changed his mind once it was clear that we could sell for big prices: Graydon was, and I believe still is, showing at H&A.

The response from the left has been much like Mr. Hedberg’s: they pretend they are too good for realism, when, as everyone with the requisite number of eyes knows, they aren’t good enough. Grace Glueck at the NYT dismissed the 911 Memorial as “a pompous piece of stagecraft”, for instance. A great artist in the 19th century might have had the standing to make some such comment, true or not, but Ms. Glueck has no such standing. Besides the fact that, artistically, she is a complete nobody and non-entity, she has spent her time up to now jabbering about work that attempts to be nothing, neither stagecraft, good or bad, nor learned, pompous or not, nor anything else. It is pretty easy to avoid criticism like hers, simply by buying into the hyper-democratic milieu she helps to sell, and offering up nothing except the tiny and pinched and humble, the social and the pitiful, the pathetic and the phony. We all know that no grand gesture of any kind or from anyone could have passed her various Modern tests, since these tests were created specifically to make broad dismissals like hers possible, with no need for argument or discussion. By the current standards, any skillful realistic depiction can be waved off with a sneer, whether it comes from Cimabue or Veronese or Leonardo himself.

The response from the left has been completely predictable, as I said: the last thing they want to see in art is any return to standards, talent, or a hierarchy based on any definable thing—that would force them into another field overnight. They have to keep playing their little games of misdirection and psychology, hoping to fool the real artists into cutting their own throats for another decade. But the response from the right, although not shocking in any way, is both illogical and disappointing. Even those that feel this is only a step in the right direction should be embracing Graydon with giant hugs. Even if it is not exactly what they were looking for in their stockings this Christmas, that is, it is still a gift of such major proportions they should never stop extolling it. This is precisely the sort of painting that should be vastly oversold in the media, if anything; and yet is has been vastly undersold, caviled and gift-horsed to an extent that can only be called tragic.

None of these educated or uneducated commentators can seem to see past their own tongues. They are like the wolf living in the winter den, surviving long months on worms and bark and bone marrow, who is thrown a steak by a passing ranger, and who turns his nose up at it because it is cow instead of the preferred reindeer. The ranger, seeing the wolf sniffing and snuffling, is tempted to yell, “It is grade-A prime, you fool. The long winter has affected your brain, you are vitamin deficient and have lost your way. Eat it and begin the long road back to health!”

No matter what else it is, Graydon’s work is grade-A prime. If you don’t like memorials to 911 or AIDS, hire him to do something else. He has done lots of lovely smaller work, but if you require giant canvases and big themes to be impressed, yoke him to your pet theme and see how he does. If he fails to fill your order, you can criticize him then, but not until then.

And if you think that all artists who take work for hire are whores, then I guess you can dismiss out of hand Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael, Rubens, Van Dyck, Goya, Rodin, Picasso, and just about every other great artist in history.

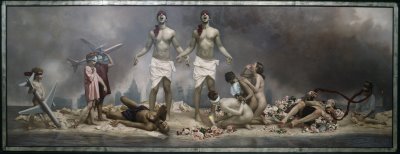

Rather than drone on and on about what shortcomings the work may or may not have, based on your narrow prejudices, why not look at what the work does right, by any fair assessment? To begin with, as a mural or memorial, it all hangs together. It is successful as a whole: meaning, it is visually convincing. None of the figures are drawn or painted poorly, none of them jump off the canvas or fail to sit in the background. The finish of the piece is consistent from corner to corner, and all the parts of the painting visually support all other parts. Technically, the piece is nearly faultless. This is not a small thing to say, in this day and age. What other large work could you say this about? It is difficult to find another 20th or 21st century analogue, to even begin the comparison—one of equal size and ambition. It can’t really be compared to anything by Diego Rivera, for instance, except in size, since Rivera never attempts this sort of realism. Rivera’s murals are pieced-together allegories, painted in a somewhat naïve mural style (purposely). I am not criticizing Rivera here, understand, just stating a fact. Graydon, on the other hand, has attempted a realistic whole here, with no elisions, no gaps, no fade-outs. That is damned difficult to do on this scale, and he has done it to near perfection. All his figures are completely worked into the background, to the highest academic standards, and the background is likewise finished, corner to corner. We don’t have the normal faded-out background, or vignetted background, or slapped-in mural background; we have a fully developed background, as in an easel painting (in fact, this is a very large easel painting, free-hanging, and framed, not a mural—it is a mural only in size).

Technically, Graydon’s thematic works are also clearly superior to Maxfield Parrish, Rockwell, Ives Gammell, and anyone else you could mention from the 20th century. Graydon’s work may be too “real” for some, but his work looks much less like a photo than his competition here. About the only contemporary things that really bear technical comparison are Odd Nerdrum’s largest canvases, but I don’t think even Nerdrum has done anything on this scale. As with Rivera, I don’t intend to compare Graydon to Nerdrum, since, beyond ambition and technical mastery, there isn’t much to compare. They aren’t even running on the same racetrack. But my point is the same: by certain standards, Graydon has attempted and successfully completed a task here that hasn’t been completed in a long, long time. Credit must be given where credit is due. To create a visual whole on this scale is extremely difficult, and there aren’t a handful of people that could do it, whatever the theme or intention. Of those handful, only Graydon has actually done it so far, with nearly perfect technical success.

Graydon’s painting is also nearly flawless as a piece of color, and this is just as rare as his other accomplishments. Murals tend to be gaudy and glaring, and the same can be said of most modern works, political or not. 99 out of 100 artists, realists as well as Moderns, appear to me to be colorblind, or nearly so. But like all of Graydon’s work that I have seen, this one is pitch-perfect. The colors are accurate and realistic; but it is much more than that, since many realistic and accurate colors are jarring and unattractive. Graydon knows how to choose a palette, and color combinations and juxtapositions that are both convincing and beautiful. Not beautiful as in, “Oh, isn’t that a beautiful bright red, hitting me in the eye like pure paint squirted from a tube!” But beautiful as in, “Everything is subtly appealing, but I am not sure why, without analyzing it. None of the tones or colors seems too much or too little, that is all I can say right now.”

The composition is also perfect. By that I don’t mean as content, but as weight. Some have used the “composition” heading to attack Graydon’s choice of models, but what I mean is that the position and direction of everything is correct. Choice of models should be addressed under the heading “content”, and, as I said, I won’t go there since I was prejudiced on content from the beginning. Choice of model will determine mood, and Graydon’s mood was determined in large part by his client. There are a majority of things he simply couldn’t have done, given the commission, so that criticizing him for not doing them is pointless. You can blame the US for being the US, but there is no reason to hoist all that blame upon Graydon’s shoulders. In terms of composition, however, the piece is completely successful. As with his other major work, on the theme of AIDS, the whole large painting here is perfectly balanced, and all parts are balanced, in weight, direction, color, tone, value, and darkness. Once again, this is no small thing. No one else has done it on this scale for decades.

Beyond this, Graydon has been critiqued for being too academic, too slick, too perfect, too real, blahblahblah. You might expect me to make the same criticism, since I like things a bit more messy in my own work. But I refuse to make it. When I paint my own political mural, I can do it my own way, with models who please me and paint that flies around the way I like it and so on. But as a critic who is trying to be objective, I am not free to just pass off all my prejudices as facts, as these critics of Graydon are doing. What seems to me more to the point on this particular topic of finish and style is that both the right and the left seem to be demanding relevance from realism. Well, there are a lot of artists who like this style, and a lot of buyers, too. A lot of people in this democracy of ours find this style compelling, for various reasons. By the modern definition of relevance, this is relevant. If art is now not a mirror of nature, but a mirror of society, then the success of Graydon’s style, both with artists and clients, must be seen as part of that mirror. That is to say, according to the rules that currently pertain in art, Graydon’s painting is not just a personal artifact, it is a social artifact. He had to have been affected by the expectations around him, by his environment. Therefore his realistic style, precisely as it differs from the realistic style of Raphael or Rubens or Leighton, must be significant.

Modern intellectuals can deconstruct nullities for days on end, but they cannot look at a genuine complex artifact (especially if it is created by someone who is competing for media attention with them, and who has not signed some contract with them) for more than a few seconds without finding some reason to throw it in the recycle bin. Now, I am not really interested in deconstructing anything. Everyone knows that I don’t believe in the modern definitions of art. But if the critics ascendant on either the left or the right currently had any consistency at all, had any connection to the theories they constantly espouse, they would have to look at Graydon’s work in a completely different way. The fact that they are so ready to dismiss it betrays some pretty transparent psychology of their own [again, more on that mystery below].

But does the Memorial create the proper mood, or any strong mood? This is impossible to answer, except as each individual person answers it for himself. Guernica is the most famous 20th century painting in this line, being a war memorial of similar dimensions, but I have always found Guernica absurd. Whenever I have seen it in person, I have always laughed outloud. I find it amusing, and I don’t mean that sardonically. I mean that it makes me laugh like a funny cartoon. In fact, it is a funny cartoon, and only the fact that others try to make it something else causes the situation to graduate to the absurd. In this honest feeling, however, I know I am outvoted 100 to 1, or maybe a million to 1. Most other people find their own ways to be deeply moved by Picasso’s painting. My point being, I guess, that Graydon or any other artist creating a public monument would be a fool to take my personal tastes into consideration, since, in doing so, he would impress one person and offend a million others. A successful war memorial or memorial to other tragedy must play to a large audience, not just an audience of top artists or critics. In taking a commission like this, an artist must consider his client’s wishes first, the public’s mood second, and the opinion of future historians a distant third. The opinions of over-educated eggheads like me and Hilton Kramer and Peter Schjeldahl don’t even come into it. It is well to remind everyone involved of this, not least Graydon himself, who has been hurt by these narrow criticisms. Graydon weighed out these priorities before he began, and he probably weighed them right: he must stick to them. The critics have always been superfluous, from their opinions on Keats’ odes to their opinions on Whistler’s nocturnes and Holman Hunt’s Jesus to their opinions on Rockwell and Wyeth. This 911 Memorial wasn’t painted to impress the eggheads on either side, so why should Graydon care that it doesn’t?*

The proper critics for an ars gratia artis easel painting are not necessarily the proper critics for a public monument. Not that there are any proper critics (a good critic is no critic), but in the case of a public monument like this, a middle-America commentary—a sort of Siskel and Ebert thumbs-up—would be more useful to magazine readers or internet surfers than an ivory tower critique from those who are invested heavily in the arguments of art one way or another. Great artists generally do their best personal work when they are painting only for themselves, or for a couple of other artists whose opinion they trust, or for some ghosts of dead artists they are trying to impress. But this 911 Memorial is not a personal work. It is a very public work, and that has to be taken into consideration. None of the critics so far have taken that into consideration. They have made no attempt to look at the piece from the public point of view. We must remember that Graydon had the public point of view in mind from the beginning, as he should. Therefore it can only fail or succeed from that public point of view. If he had been interested in impressing only himself or a couple of ghosts, he wouldn’t have taken the commission in the first place. If he had set out to impress art critics, we could only call him a fool. No, to discover his success, we must ask the public—this is a public monument, after all.

By these standards, there is no future, no hope. The dead-end of the right is just as dead as the left, since although the right appears to have a program based on statable standards, as at The New Criterion, there is no hope of realizing it. Not because it is so high or puissant, but because it is contradictory and confused. Kramer’s ideal leads him somehow to Nerdrum, so how consistent can it be? Other critics would serve up someone like Bravo, who paints paper packages: how is this preferable to Graydon in any way? And as Hughes has moved right—trying to take Freud with him—he has lost all his air (which was quite a deflation). He can almost visibly be seen bashing his head against a wall, the very wall I am talking about. He wants craft, but doesn’t want any derivation or historical reversion or political backsliding: he wants a new Leonardo to arrive, fully formed, and updated in all the right ways at once—and he wants this Leonardo to come to him and bow down and ask for anointment from him, the critic. Good luck, Sir.

Kramer and Hughes and all the rest of these lazy critics won’t get in the car or do a websearch, won’t look at people like Graydon until they are served up hot by the New York Times or the London Times, by Nicolas Serota or Phillippe de Montebello, and even then won’t give them a fair shake. If Graydon doesn’t instantly outstrip Goya and Velasquez combined, sprinkled with the “relevance” of Bacon, then they think it best to return to their whining about Hirst or the Chapman Brothers.

The logical response to Graydon is to give him a pass on the subject. If you like it, fine, say some nice things. If not, wait for the next subject. You wouldn’t have liked all of Gericault’s subjects as they came out each year, or Goya’s, or Chardin’s, or Picasso’s, or whoever you like. But, for heaven’s sake, try to see the bigger picture, which is precisely this: Graydon is highly educated, earnest, and prodigiously talented. He is not a sell-out or a phony. That is so rare now in art it calls for almost immediate deification. Relative to the constant guff about nothing we get these days, Graydon deserves an immediate stopping of the presses, his own after-shave, and a year-long one-man show pre-empting American Idol. Police horns all over the nation should go off and the Emergency Broadcast Network should come on and tell people that art is officially no longer dead.

Again, speaking relatively, if Pollock’s dribble is worth 140 million, we would have to bankrupt the Pentagon cutting Graydon a check for his next canvas. If Graydon is, say, 100 times better than Pollock, then that is what, 14 billion? Start saving now. All these things with such huge pricetags, the Naumans and Koons and Hirsts, will be worth pennies in a few decades, or will be pitched into the sea as flotsam to feed the fishes; but Graydon’s works will survive. How he will fare against Bouguereau or Millais or Waterhouse is yet to be seen, but any fool can see that he is already better than his ancestor Maxfield, already better than Rockwell and Ives and Lack, already better than all the phony Moderns with their assemblages and poses and empty constructs. He has climbed out above that already, and future generations will see him competing only with the Wyeths, and with other realists emerging now—Wang, Collins, etc.

Technically his canvases are a marvel, no less, and if you can’t see this you are either an artist yourself—strapped blindly to your own technique (as you should be, really)—or you are a narrow-minded ideologue of one sort or another. That artists are lost in their own little worlds is to be expected; but when critics and art administrators have no breadth or depth of vision, we have major problems. We have major problems. The main problem being that the commentary and administering is being done by people who are not qualified to be doing it.

Now, if these critics and art administrators had something better than Graydon to promote instead, I might be able to read their critiques without fear and trembling, without nausea, without feeling like a stranger in a strange land. If these Leviathans of taste and cunning could finish all their cutting remarks by saying, “and here is a drawing I just did that is so much better than Graydon, so much more the direction art should be going,” I might be able to calm my mortal coils, to stop sounding furious. But no. I guess everyone needs reminding that these critics and administrators are sitting on no gems. Their pouches are empty. They have no portfolios of their own, and can point to no portfolios. They have negative words in a net bag, tied with a string, and that is all. If we don’t like Graydon, we can go back to sharks in tanks and reglued plastic dolls and vials of warm blood and piles of sand and colored squares. No sense letting Graydon and his fellows lead us back in the direction of sanity, when we can continue to talk about excrement and lotto tickets lovingly and continue to extol empty or slashed canvases and continue to rape ourselves on burning piles of rubbish.

Considering the alternative (and we have been considering it, for about 9 decades now), Graydon should be given ticker-tape parades, the key to the city, and free vending machine access for life. We have been feting fools for nothing, promoting peabodies and slugs into seven figures for near a century, and now someone comes along who can bear promotion without the god’s grimacing, and we prefer to look the other way. Because Graydon, in his 30’s, doesn’t impress each and all as much Giotto, Titian, and Ingres, we prefer to belittle him and keep looking. Rather than welcome him as the long lost prodigal, the outcast returning, and encourage him to climb back into the Pantheon, and take us with him, we prefer to nitpick him into madness and go back to our nobodies, our Lilliputian dreams and claustrophobic journals.

For example, Graydon had the misfortune at the end of last year to be subjected to an interview at NPR with Karen Michel. She began the interview by telling us that Graydon is gay and handsome. How is that pertinent? It is so distastefully Modern, before we even start talking about art, that it makes my head spin. Might she feel free to begin an interview with me by telling the audience I was straight and ugly? Who knows, she might. If the interview had concerned Graydon’s large work on the subject of AIDS, then his sexuality might possibly have been pertinent (although, last I heard, straight people were free to paint about AIDS as well). But Graydon’s sexual preference had nothing to do with 911, or with anything that could possibly impact this interview. Therefore, one must assume he was either getting points added or subtracted for no reason. Since the interview was a hit piece, we must assume this information was included to prejudice us against Graydon. It is not clear that it would do so, with NPR’s audience, but the thinking of these strange people is not always easy to unravel. Because he is a realist, they had decided to slant the whole piece against him in the baldest way imaginable. Perhaps they just forgot that most people who hate realists offhand don’t hate gays offhand: they didn’t have all their slurs in order. Or maybe they just thought that only the New Criterion was listening [once again, see below].

In a part of the interview that was edited out, Ms. Michel had the audacity to steer the conversation to Robert Ryman, a painter of white canvases (I find this interesting, since I have just written about Ryman). This is the sort of transparent and malicious rudeness that might have been seen by a interviewer of the Buddha, saying, “you know, Gautama, I always loved Mohammed, would you mind if I asked you some questions about the Koran?” Graydon should have said, “Are we live? Yes? Well, I have a question for you. How does someone so gloriously ignorant and contemptuous of a subject get hired to do an interview on it? Have you seen my painting in person? No? Then what, exactly, qualifies you to ask me any questions at all? Does NPR pull these shows out of a hat? Tell me the truth—you were just walking by the water fountain and Amy Goodman gave you a microphone and pushed you through that door, right? Without looking at that paper, tell me my last name.”

For the record, Graydon said he thought Ryman’s canvases were "empty." Ms. Michel thought them "very full." Something is very full of something here, but it isn’t Ryman’s canvases.

Perhaps the lowest moment of the interview, even below the question about Ryman, was Ms. Michel’s implication that there was something unsubtle about the New Britain museum including a text to help viewers with the references, a sort of annotation of the painting. This from someone who prefers the avant garde, where we have nothing but the annotation, where we have a book-length text supporting something liked a dead frog. At least Graydon’s painting had some real references that might bear discovering; with the avant garde the text has to manufacture everything from less than scratch.

James Panero also complains of the same thing at New Criterion, although we must assume that Mr. Panero is not coming from the left like Ms. Michel. He doesn’t like blurbs; nor do I. But I don’t find the inclusion of a text here to be a strong argument against the painting. In this case some annotation may be helpful. If not, don’t read it: it is not on an audiotape you have to pay for. As with my Shelley Altarpiece, not all viewers will know what they need to know to get the full effect. The literature is for these people: to answer questions that do actually come up. Annotation is only a nuisance when it is more creative than the work itself, when it must be looked to for any meaning. The New Britain’s annotation does not fall to this criticism, since it simply clarifies (for some people) things that are already clearly in the painting (for other people). In a reply to Mr. Panero published at New Criterion, Charles Lancaster from the Lyme Academy gets the last word on this topic: he points out that no one complains of annotation to Dante or Joyce. Joyce is both the most-annotated and the most-feted author of the last century. Why can Modern intellectuals stomach flighty and false annotation of avant garde nullities and extended annotation of “interior novels” but not stomach four pages of straightforward information? Again, there is some misdirection going on here, and we are now ready to address it.

The other of two letters published at New Criterion in response to Mr. Panero’s article accuses Graydon of making some use of a "gay bathhouse" in his painting of the 911 Memorial. I can only imagine that this reader finds something offensive in the two main figures in the Memorial, although they don’t look gay to me (Ms. Michel twice calls them “buff” in the NPR interview, although they are not buff, either, by normal standards—would she prefer a couple of fat hairy guys standing in for the twin towers?—maybe Jason Alexander and John Goodman as WTC1 and 2—she might. Ms. Glueck at the NYT called them “preppy”, another non sequitur. Preppy is a style of clothing, and these guys aren’t wearing any. How does one wear a loincloth and a blindfold in a preppy manner? If the critics don’t like these boys, they need to be a little bit more specific, and accurate: they need to choose their adjectives so that these adjectives impact Graydon and not their own abilities as writers and thinkers). But what I can’t imagine is why New Criterion printed this letter. What we have is a homophobic moron writing in to agree with everything Mr. Panero said. Is Mr. Panero proud to find that homophobic morons agree with him about everything? Maybe he is.

This is obviously fallout from the AIDS Memorial Graydon did several years ago. All the homophobes and pseudo-Christians are still in a huff about that, seemingly, with New Criterion using this as an opportunity to slip in a couple of late, well concealed jabs. But Mr. Panero’s wimpy little voice on the radio, as well as his wimpy attacks in print, don’t really provide the necessary cover for his true opinions. He fails to convince us (or me, at least) that his stated reasons are his real reasons. His argument just doesn’t add up, and you are left reading between the lines, trying to get the real story.

Take, for another example, Mr. Panero’s comments on New Realism as a whole. He quotes Mr. Cooper at the Newington Cropsy saying,

And then responds: "Really? Modernism stripped all of that away?" Mr. Panero’s glib dismissal of Mr. Cooper’s point betrays a refusal to actually look at Graydon’s work, or to take anything that surrounds it seriously. Why, we are not sure. But, though Mr. Cooper’s comment may be couched in imprecise or exclamatory language, its gist is clear, and its gist is true. Yes, Modernism has stripped away all that. It may have nothing much to do with William James or unseen truths, but Modernism did not just accidentally deconstruct every pre-20th century category. The old order has been purposely stripped away, in all its forms: some will miss some forms and some others, but all of them are obsolete or obsolescent.

Here is another clipped argument from Mr. Panero that doesn’t make much sense: “It [the 911 Memorial] is a machine for illustrating technical skill, far more than it is a moving memorial to September 11.” It is interesting to remember that Clement Greenberg said the same thing about the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel: he claimed it was more a technical achievement than an artistic achievement. This claim, like all of Greenberg’s manufactured claims, is so absurd and so clearly false that you must ask what his motive was for asserting it. He couldn’t say what he meant, which was that he wanted to destroy Michelangelo so that others could take his place (the dream of Dada). So he just concocted a series of airy assertions that might stand, at short notice, as an argument—being careful to choose assertions that Modern people already wanted to believe. Mr. Panero, though not as historically ambitious as Greenberg (I hope, for his own sake), is practicing some similar misdirection: he intends to promote someone other than Graydon, for reasons mostly unknown to us, so he must cut Graydon down with any set of sentences he can think up at short notice. Although he has no reason to think that Graydon is just showing off here, and gives us no reason or proof of that assertion, he states it anyway. At a time when almost everyone is jealous of technical skill, at a time when ressentiment is at its peak, this is another cliché that is sure to catch the majority, another slur that is certain to remain unanalyzed by all.

Mutatis mutandis, the same can be said of James Cooper, as I hinted above. With any cursory perusal of the Newington Cropsy website, one must discover that they are a Christian organization. Of course, this can either be good or bad. But when their spokesman leads with the argument that Graydon is not Raphael, we are led pretty quickly to the possibility that we are being misdirected for some reason. As I just showed with Greenberg, when people say things that don’t make any sense, or that are gloriously beside the point, it is usually either because they are absolute fools or because they don’t want to tell you what they are really up to. We will give Mr. Cooper the benefit of the doubt here and assume he is just dodging. He can’t really expect that Graydon would be Raphael, and he can’t really expect us to believe that he is not going to look up from his duties at the Foundation until a new Raphael arrives and drops a load of paintings directly into his lap. So he must mean something else. As with Mr. Panero, the fact that he allowed his quote to be used in what everyone must have known was going to be a hit piece means that he probably would like to see Graydon stumble. I can’t prove any of this, of course, but both Nietzsche and Sherlock Holmes would back me up here, I think. The psychological and physical evidence all points in the same direction.

Now, many may be surprised to see me taking this side here, since I was notorious in Austin in the 1990’s for my attacks on the "Day Without Art." On this website I have a couple of letters to the editor that ridicule that whole concept. But I have never had the least problem with Graydon’s AIDS Memorial, as a piece of politics. In fact, in my old letters, I say explicitly that this sort of work would be the proper artistic response to the tragedy, rather than an infantile draping of art with plastic baggies, and a necessary link between art and homosexuality. I am never personally very interested in political art, no matter what the subject, but I am neither surprised nor offended that Graydon painted his painting, or that he did it the way he did it. All that is his artistic call, of course, and, judged by the standards such a work must be judged by, it is a near perfect success. I might have done a couple of things differently, but, again, so what? Graydon paints his paintings and I paint mine, and we have no plans to change that.

Just think how bored people must be to listen to talk shows like NPR or to read journals like New Criterion—and to admit it (and these places, like the New Yorker, are supposed to be for intellectuals). People’s standards have dropped so much in the past score of years that they will listen to conversation which, until recently, would have been considered gibberish. I have seen and heard a few other sensible people being interviewed on TV or radio, and they seem like fish on the wrong side of a fishbowl, gasping for air, trying desperately to find some meaningful word or idea on which to hook a fin, and finding nothing. The level of discourse is sub-collegiate, no, sub-secondary school. I have heard more rational repartee from the Little Rascals.

The NPR interview was five minutes of nothing. Ms. Michel never even spoke to Graydon, in the part that made it to the airwaves. Graydon is heard twice, once reading two lines from the Slow Art manifesto, and then again saying something off-the-cuff about the Titanic. It is clear as sunshine that NPR edited him down to his least appealing 15 seconds, and then surrounded that with negative chatter. Who on God’s Green Earth wants to hear that, except a bunch of losers practicing for the Brave New World? Who on either side of any argument could benefit from that?

Mr. Panero’s critique of Graydon was nearly as empty, and equally transparent. Just look at the length. Who can say anything given only two pages? Or look at his interview with Jacob Collins. He asks him nothing: what did you have for breakfast, what size shoes are those, what time is it? The whole world is moving toward the blog or the soundbite. Everything must be short and breezy and informal, digestable over a PowerBar in the car or a quick espresso while wireless at Starbucks. Beyond this, the people involved have become smaller and smaller. Soon they won’t even speak to eachother, they will just squeak and eat cheese.

About Ms. Michel or Mr. Panero, one can’t help but think—as J.M. Barrie said of Smee—“I know not why he was so infinitely pathetic, unless it were because he was so pathetically unaware of it.” These are the kind of people who now gravitate to the arts and media, and no one ever makes them accountable for anything. For some reason, people keep tuning in. One is reminded of the Gary Larson cartoon called “After Television” where the family is sitting in the living room watching a blank wall. We already have Ryman’s white canvases; what kind of stretch is it to have a white screen? The screen is as good as white already. One could erase Graydon’s interview with one wipe of a small rag, one quick pass with an artgum. All conversation and commentary has become negative space, a static drone.

This is precisely why Andrew Wyeth never did any of these interviews, why J.D. Salinger bowed out of the world 40 years ago. But Wyeth was able to get on without them; PR was an entirely different beast then—just 50 years ago—a beast of much smaller proportions, with far fewer teeth and much less of the smell of wet fur. Like the Buddha, Wyeth had the fortune to predate the age of the interview, the age of the all-engulfing, all-deciding media. Even with a famous name, it appears Graydon thinks he cannot get where he needs and deserves to be without the proper promotion. He is competing with empty husks who are promoted by the deepest and most unscrupulous pockets ever known to history. Even though his pod be full to bursting, he cannot be expected to make any headway against this current—at least in his lifetime—without some major rowing from his crew.

One would think they could portage this boat into a smaller, clearer running stream—the kind of little backwater Wyeth spent his life in—but that thought appears to have devolved into another species of naivete. Like all air above us, all water is interconnected, and even the smallest rill is now polluted. You can climb the tallest mountain and begin your journey from the spring itself, from the very snow’s edge, it will not matter: as soon as the prow touches water, some Modern moron will poke his head out of the spring to bite your oar and shred your sail, some deconstructing dipshit will crawl from the snow and begin coughing her noxious phlegm into your ear. That will be the signal for a host of chorusing crickets to arise from the rocks, chirping pamphlets at you and singing your superego into utter submission under the rub of some pseudo-religion or pseudo-politics.

The self-appointed experts on both sides of the road can argue about specific points in Graydon’s work, and in other new realism, but the bottom line is that if Graydon cannot be encouraged and held up as an example to younger artists (instead of the empty heroes of the avant garde), we cannot expect any improvement in the arts in the near future. We should not be comparing Graydon to Raphael, we should be comparing him—as a prototype of the artist now—to Bruce Nauman and Damien Hirst and Robert Rauschenberg and Odd Nerdrum and Lucian Freud and Jenny Saville and John Currin and Claudio Bravo. I don’t know either Graydon or his work that well: he may be flawed in any number of ways. But the rest of these people are fakes and phonies of the most extravagant sort, people whose ambitions and motives are always suspect and often disgusting. If we waste Graydon, as we have wasted so many lesser talents, we will have no one to blame but ourselves. We will deserve the ever-widening desert we have created, the bugs and bones and brittle bark (and paper bags) we must survive upon, the wind-blasted cave we will huddle in, continuing our deconstructing to the bitter end by pulverizing the very stones we sleep upon.**

That was for the critics, but for Graydon I have this to say: you don’t need these people anyway! Avoid them like the plagues they are. They are rotten bridges to nowhere. You need a few good clients and your freedom—the rest is nothing but a drain upon you. Word-of-mouth can still outtalk this propaganda from either side, the hit pieces and constant drone of misdirection. A few true words from a real person can trump an entire publishing empire. These institutions overrate themselves. It does not matter if 100,000 are listening to the white noise of NPR or the New Yorker or CNN or ARTnews, or if a million are—white noise is white noise and it does not adhere to the brain or the spirit. Numbers mean nothing, as Thoreau taught us. It is more important to do something real, that one person sees, than to do something fake, that 100 million see. The fake thing will be erased by the wind very soon, but the real thing will take root and persist. That is the way the world works. Fake things have to be reinvented and re-released every other morning, to keep the population up; but real things are rare, they don’t beget and multiply, they don’t advertise, they don’t hang out on the street corner. If they are worthy of life, they keep waking up: the Muse pinches them each morning for the general good.

The way you can tell a real thing is that when it is ignored, it is the ones who ignore it who suffer, not the thing that is ignored. If the Modern critics ignore real art, then it is they who have to live without it, they who suffer. We, as the artists, still get to create it and to live with it, whether it sells or not. We suffer only insofar as the gift of the Muse fails to satisfy us: and as far as we are true artists, how could it? We have sought true art and we have found it—as artists we are blessed to the limit of blessing.

*To be perfectly clear, the 911 Memorial never made me want to laugh. That was not the point of my Guernica comparison.

**And by “we”, I mean you, you mudbrained Moderns, you children of the 20th century. Personally, I was hatched from an ancient egg, and am blameless.

Addendum: James Cooper of the Newington Cropsy finally got around to reading this in September of 2008 and writing me a response. He said I was wrong about Graydon, who was nothing next to Jacob Collins. Then he said my work was also nothing as far as he could see (although I don't think he has ever seen it, except on this site: that's a careful critic for you, dismissing an entire body of work based on a 30-second pass through a website). He then asked me what my criteria of art were. This proves he hasn't looked at this website for more than a few minutes—enough to see his own name—since I have about 50 articles listing my criteria about every last thing in the universe. I am known as the most opinionated person in art, but he can't find my criteria. I told him, "My one and only criterion of art is that the less talented should remain silent in the presence of the more talented: so shut the fuck up!" That seemed to do the trick. I haven't heard from him since, which is just the way I want it. I welcome the input of all qualified people, but I don't include critics in that list. Like Whistler, I consider them to be presumptuous interlopers who don't even deserve a serious response. In fact, they deserve to be shunned and ridiculed. I do my best in that regard.

If this paper was useful to you in any way, please consider donating a dollar (or more) to the SAVE THE ARTISTS FOUNDATION. This will allow me to continue writing these "unpublishable" things. Don't be confused by paying Melisa Smith--that is just one of my many noms de plume. If you are a Paypal user, there is no fee; so it might be worth your while to become one. Otherwise they will rob us 33 cents for each transaction.