return to updates A Review of the

return to homepage

Paul Oxborough Exhibition

London

by Miles Mathis

This is the first in a planned series of reviews of contemporary exhibits. Since I have not seen five sensible words together printed in the mainstream press on art in my lifetime, I now leap into that void and try to kick it into some useful form. That is what artists do, you know, one way or another. They fill voids, or look like fools trying to. Most modern people with any education believe it makes more sense to keep quiet, but artists are not modern people. They retain the perhaps indefensible view that it is better to try and fail than to do nothing. They are not especially scared of looking like fools, since only fools fall in love, make realist art, have strong opinions, etc. In short, people who were not scared of looking like fools did everything that has ever been done. Besides, I am reminded of what J.D. Salinger once said, in effect: If you want to read a page and can’t find it, write it yourself. If no one else will tell you an interesting story, tell yourself one. If no one else will speak sense, speak sense yourself, if only to yourself. Which is as much to say, if you leave this page in disgust, I will still be here, amusing the ever-lovely Muse.

I have claimed in a hundred places, sometimes at top volume, that art criticism is, or should be, the duty of artists. All other criticism or commentary is unqualified at best and nefarious at worst. Historically we are in the belly of “at worst.” Every single word published by publishers of all kinds is now absolute bollocks of some sort, and the more famous it is the more wicked. I don’t deny that there are other poor neglected souls shivering in the wilderness, saying things that are true and helpful. But you aren’t likely to have met them or heard them either. The mainstream does a very efficient job making sure of that. If the words you are reading have been edited by anyone anywhere they are probably not worth reading. They have been watered down so as not to offend your neighbor, and the odds that they have any real content are near zero. The more you are paying for your information, the more worthless it is. You are paying the salaries of lines of editors who justify their existence by bowdlerizing and eviscerating everything they touch. Committees do not have opinions, they have averaged agendas, which are as useful to real people as diet cola or plastic furniture.

All of which is a rather odd lead-in to a review. . . so all the better. The long and short of it is that I believe I am in a pretty good position to say interesting and meaningful things about Paul Oxborough. In fact, there probably aren’t five people in the world in a better position to tell you why you should go to his exhibitions, buy his paintings, and what to look for when you do. The reason for this is that I am what I call an “accidental peer”. I don’t know Paul, have never met or spoken to him, didn’t go to school with him, know nothing about him personally, and have no financial ties to him. I have never shared gallery space with him or even traded recipes for varnish. Despite all that he and I have much in common. He is someone I can comment on with real sympathy. Paul and I are about the same age and we both were weaned, at least partially, on Ratcliff’s Sargent book. We share this distinction, I imagine, with Dan Gerhartz and Steven Levin and Scott Burdick and many others. Although we come from different places, all of us emerged in the 90’s. And although we are now moving our separate ways, a review of specific paintings from the 90’s might convince someone that we all graduated from the same atelier.

One might say that Oxborough has kept to Sargent better than the rest of us. Gerhartz pushed through Schmid to Sorolla and then to a use of color that is more like Jamie Wyeth than anything else I can think of, with that use of straight yellow and a current predilection for all stronger tones. I have gone the opposite direction, reversing into grays and browns and often tightening my brushwork, influenced by Whistler and Titian and many others. But Oxborough has remained true to the faith, continuing to learn more from Sargent with each passing year.

[This review is of the Albemarle Gallery exhibition in London in October 2005. Readers can follow my commentary by referring to the images on the gallery website. All other Oxborough images cited may be found at the Eleanor Ettinger website. I saw the London show in person and have seen several of Oxborough’s shows at Eleanor Ettinger in New York, so be assured this review is not based only upon webimages.] Oxborough’s ties to Sargent are gloriously clear in his views of Venice. I mean this as no slight, since there is no pastiche in these works, and having debts is a good sign, not the reverse. For example, a small oil called Gondolas is a perfect gem, worthy of Sargent himself but by no means a knock-off. The colors are high without being too high, and the brushwork fits the size of the piece like a glove fits a master’s hand. Venice at Night is also clever—a successful little nightscene. And three others from Venice are also satisfying: Laundry, In the Chapel, and Alleyway. All are small and brilliantly off-hand. They impress without chucking you under the chin.

Of Oxborough’s other work featured on the website, Spring is the most successful, I think. He cuts off a foot and the most obvious hand could have a bit more definition, even as a sketch, but the main head is smashing and Oxborough somehow makes horizontal stripes work. As a piece of color harmony it is perfect, and the feel is peaceful and real without being flabby or sentimental. Cuddle is another charmer, one of Oxborough’s golden paintings that borrows from Sargent’s Artist in his Studio (Boston MFA) and takes it to new places. Before Bed is yet another, with lots of lovely yellow sheets. As a sample of brushwork, it is stunning, and one could only critique it on the basis of content.

Self Portrait with Drawings is another success.

Perfect color harmony, effortless brush, and enough subject interest to hold it all together. Such paintings tend to teeter into a focusless morass of detail, and this one veers momentarily in that direction; but it does not fall. The most jarring note—the blue bottle—fails to harmonize, pulls us away from the focus and the main lines of movement for no apparent reason. It is not so much the blue as it is the modernity of the “thing”. One intuitively hates the thing for its ugly label; asks if it is plastic. But there is so much good here it is easy to forgive, if not to forget.

One of the stars of the show—based on size—is Repose in Blue, Silver and Gold (21” x 36”). Once again a reviewer finds nothing to complain of in color harmony or brushwork. But somehow the work fails to generate any real excitement. I believe this is because the sofa spread is more impressive in all ways than the girl, and this is not how it should be. It is not that she is not gorgeous, it is that she is not featured. She is covered by a plain black dress and her face, though error-free, has no special claims to attention. In fact, her feet are far more enticing, for reasons of composition and lighting more than anything. But the focus of the painting is the shine on the spread. This turns the painting inside out. The stripes don’t work here either, since they also confuse the eye. Oxborough has, in a masterly manner, painted a complex pattern over a stripe. But its effect in the end is to usurp the natural focus of the painting, which should be on the girl.

Jade and Gold is upside down in much the same way. The coat overwhelms the woman, and her small eyes look all the smaller, despite the mascara. We have perfect color and brushwork, but not really a convincing focus. The hand looks like it has been moved, but it is still not clearly in the right place. Oxborough has kept it on the canvas by main force.

Most of the rest of the works in the show are Oxborough’s signature restaurant scenes, which I find fatally banal. All share the lovely brushwork of Sargent’s Breakfast Table (at Harvard), but none have its charm. Sargent’s work is already on the edge of banality, being only an exposition of glassware and china with a dashed-off head. Oxborough downgrades this with fake orange lighting and frivolous NY people, leaving us hungry for content.

I stated in passing above that Before Bed could only be critiqued on its content, and I believe that is the case with most of Oxborough’s work. In my opinion a painting should not be as easy to digest as a snapshot, and some of Oxborough’s work is just too light. The two models in Before Bed are throwaways; they have no artistic weight. You could get as compelling models and poses in any bedroom in the world, and I do not mean this as a compliment to democracy or equal-time. The girls are not as interesting as the sheets, and this is not how it should be. The restaurant scenes take this to its limit: there is nothing but brushwork here, and that is just not enough.

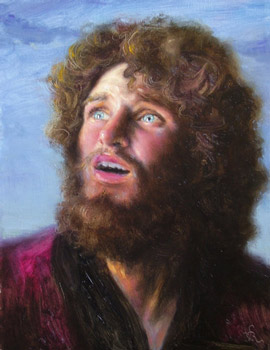

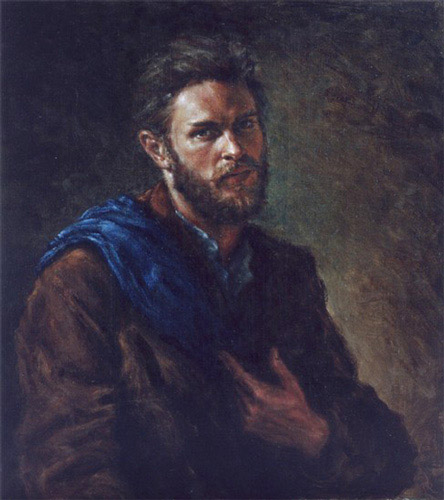

Oxborough’s many self portraits also confirm this. Mystifyingly, they are some of his weakest work. He seems completely uninterested in his own character. Once again he is studying the light, and world, bouncing off him, and can’t seem to be bothered to look into his own eyes. He is always at a distance. When he is not pretending to be Robert Louis Stevenson he is just a blank face, two inches square. The only time we get a closer look he is pulling a monkeyface, as if he absolutely will not give anything away. This is not what a self portrait was meant to be. Forget Rembrandt or Van Gogh, just look at this self portrait by my friend Van Nielsen.

Nothing being held back there, baby. If that is too intense for you, try this one.

We get a lifesize head where we can see the eyes, and the eyes and pose are telling us the whole story. That is the sort of thing we want from a self portrait, not some little dash and dab thing that was painted with a cup of sugarcoffee in hand.

One also has to wonder about the precise genesis of the 6 x 8 in. cow painting. I doubt there is any precedent for it in art history before Santa Fe, circa 1975. I mean particularly the little 15-minute affair, where pretty blobs of paint sort of mimic cow shapes or cloud shapes or shadows. The idea for this probably came from looking at Sargent as well, although I can’t remember that he ever took it to this ridiculous limit. Sketching is great, but these things aren’t sketches. They are intended as finished products and are cranked out just for the known market. They differ from Whistler’s tiny little paintings and pastels in that Whistler was really interested in capturing a mood. But these new “sketches” simply act as paint samples. They say to the buyer, “look at my brush flit about, aha!” and nothing more.

I don’t know it for a fact but I suspect Oxborough’s galleries have pushed him in this angelfood cake direction, since harmless little scenes and whatnot seem to sell well, for reasons beyond my personal comprehension. Whereas I could see buying Hot Fudge Sundaes

to hang in a sunny happy room, I cannot fathom the appeal, to artist or buyer, of a work like The Bartenders or Bistro or Dark Bar. Who pays top dollar for a blurry nothing like this? Apparently a lot of people. Eleanor Ettinger and a thousand other galleries are littered with this sort of thing, so people’s homes must be too. New illustrators, hatched as if my magic, arrive every year to supply the constant demand for 12” x 15” interiors and café scenes; Oxborough is only the current sales leader in this category. The same market that threatens to corrupt Oxborough and his Ettinger comrades on the east coast is threatening Jeremy Lipking on the west and many others in between. I myself have had several galleries ask for local scenes like this—to sell to the clueless tourists, I guess. In Munich they want scenes of Munich, in Prague they want Prague, in NY they want NY, and in Oklahoma City they want. . . anything but Oklahoma City. I am sure that Oxborough has a family to feed, blah blah, but now he also has me reminding him that he is much too talented to waste his time with puff pieces. He has hit forty, he has the big studio and money in the bank. Time for him to really air it out, to show us what he can do. And I don’t mean technically. I mean in terms of content. In terms of emotion and artistic depth. Of his larger works, only Silver and Green

really impresses me. The rest of them appear rushed, as if the galleries are giving him quotas. He is too young to be plagiarizing himself already. He seems to be selling almost everything he paints now, and that can be a terrible pressure. I have seen it destroy many artists. Galleries don’t like to be out of stock, and once your backlog is gone, you are back-to-the-wall.

The hardest works to get done under such pressure are the large ones. You can’t dash off a large work like you can a small. Ideally you have to hunt for models, dig for ideas, research poses and compositions, stare at the ceiling for inspiration, wait for appointments. If you have Oxborough’s hand all you need for a small work these days is a good photo. I have heard other artists scold him for using photos, but I don’t go there. I don’t care if he is using photos or camera obscuras or holograms beamed from alien spacecraft. I am only concerned with the finished product. Whether the model sat there the whole time is not the point. The point is that the paintings, beyond the paint, rarely have any artistic purchase. They have no emotional weight. No matter what size, they come off as studies of light. There is more to art than studying light, my friend. I don’t deny him the right to his Hot Fudge Sundaes, which I like as much as anyone. But an artist cannot build a lasting reputation on such work. All I ask is that he leaven the lump occasionally with something that stays with you longer than a meal or a smoke. I am not asking for Executions on the Third of May (Goya) day in day out. I mean, even Van Gogh didn’t create a Starry Night every week. But at the very least I think Oxborough is capable of a Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose (Sargent) or a Mending the Sails (Sorolla). If he can do Hot Fudge Sundaes he can do anything. Honestly. But it is going to take some doing. Planning ahead, real model time, and the galleries off his back. You can’t produce 30 Mending the Sails per year.

Now, Mending the Sails and Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose aren’t generally considered the deepest works in the world. But they manage their large displays of bravura technique without a note of falsity. They don’t aspire to any great content, but they avoid being superficial by at least being honest and non-theatrical. They transcend illustration. They may be manufactured, but they don’t look it. In short, they have a bit of character, a character lacking in almost all contemporary realism. Sargent has always been accused of basically being a rich momma’s boy, painting frivolous upper-class twits. But many of his portraits prove this to be false. The portrait of his father is heart-breaking—the man is so clearly overcome by despair. Or his pencil portrait of Vernon Lee—there is a real person there, and a real connection. Gitana is awash in some mysterious emotion, as are Capri Girl and Carmela Bertagna. Many will say it is unfair of me to compare Oxborough to Sargent, but notice that I am not making technical comparisons. Technically Oxborough is often very near Sargent, and there is rarely anything to complain of regardless. The comparison I am making is one of depth of character. The place to best see this is in the non-commissioned work, and that is why I have gone to Sargent’s portraits of family and friends. All of Oxborough’s work is non-commissioned. We are told the models are mostly family. But a viewer would never know it. I have read that his wife Jenny is in many of the works, but I couldn’t say who she is. I am guessing she is the one in Green and Gold, but this is the only portrait that gives her more than a dead stare. In the bed and hotel scenes like Room Service and The Hotel Grand she is ragdoll, an almost anonymous lump in the white. We have no idea who she is or how the artist feels about her. She is an artistic prop, a reflector of light. He says in his CNN interview that these are napping or pre-napping poses with Jenny. Well, he needs to wake her up, and pinch himself while he’s at it. Compare these works to Stieglitz’s photos of O’Keeffe or Wyeth’s paintings of Helga. I don’t expect every artist to be as great as Stieglitz or Wyeth, but Oxborough isn’t even trying. He seems satisfied with this superficial little world of room service and after-dinner drinks in Manhattan, a permanent little void where no one is really paying attention.

Which brings up another question. Where was Oxborough in the early 90’s? He is the same age as Gerhartz, but Gerhartz was where Oxborough is now ten years earlier, selling out shows in the southwest with the same sort of gorgeous paint. Linda McAdoo in Santa Fe helped launch Gerhartz, and although I don’t think she sold 100 paintings for him, he certainly had major buzz and made good money. On a slightly smaller scale Quast and Jan Ballew were doing the same for me. This was 1992-93, and Quang Ho was emerging strongly in Denver and Taos. And many other artists in their 20’s. Where was Oxborough? According to the interview and bio, he was out of school by 23, that would be 1988. He landed a local gallery in 1995 and was discovered by Ettinger in 1998. We are told he traveled about Europe, but for seven years? I don’t think so. Some will jump to the conclusion that I am implying he had a black period, was in rehab or jail or something. Just the opposite. I think he would have benefited from a black period, starving in a garret with his heart broken, fighting in the Gulf War, or strung out on methadone and twinkies. As it is, his paintings give the impression of someone who married his high school sweetheart, has never had a callous or a scar, who doesn’t read, and who won’t eat a carrot or a potato unless his Mom peeled it. Now, I don’t wish a hard life on anyone, but even a guy blessed by good fortune might find more emotions in the world than just napping and eating hot fudge sundaes. Woody Allen, blessed in most ways, said if you live in the modern world and aren’t depressed, you aren’t paying attention. And if you live in NYC and aren’t conflicted in some way, you must be a moron. Once again, I stress that I am not demanding angst or brutality or sordidness as proof of depth or intelligence. But there is no richness to Oxborough’s beauties, and it is precisely because they seem completely untouched by sadness or pain or loss, by complexity of any kind. A Café Named Desire comes nearest having some sadness in it, but maybe she is just sleepy from the pose. At any rate, that painting is more than five years old—Oxborough has since ditched even that small amount of melancholy. And compared to the painting it is probably based upon, Degas’ L’Absinthe, it is a very weak drink.

Of course Oxborough really is the cream of his little crop at Ettinger and Albemarle, despite all this. There often isn’t much to bite on, but it never bottoms out altogether, even with the cows. Even at his most bourgeois, at least Oxborough isn’t painting repellent couples shopping at Tiffanys, like Iain Faulkner, or dressed in tuxedos looking at the computer, like Stuart Gatherer. Paintings like these look like a parody of Wall Street realism by John Currin or something, but I have to believe they are meant seriously. They make you question the bent of the whole gallery.

Oxborough not only has a problem with depth, he has a problem with size. Dan Gerhartz has hit us with Hind’s Feet and Awaiting his Return, both of which score A’s for ambition. Oxborough’s largest works Café Concert, In the Dressing Room, Dance, The Palace Ballroom, and At the Spanish Hotel do not. They are not well-thought-out compositions, they are just large snapshots instead of small ones. With her Dogs (34” x 44”, pictured top of this page) is probably the closest to having the sort of gravity that a larger work requires, and Oxborough has even tightened his brushwork here just a bit, which was the right thing to do. The hands and feet are lovely and the painting is successful in many other ways. But it is still not what we can expect from Oxborough at his very best, I think. The fact that he cut off that beautiful foot really bothers me, for instance. I can't forgive him for it. He wants to make us think he is daring for cropping half a foot and 1/4 of a dog, but the painting is actually fairly bland as a composition, since the lines are all square to the frame. Meaning that we are looking straight on at the bed, so that both the headboard and footboard are level, to the frame and to eachother. This is the easiest way to do it, but it doesn't give him the opportunity to create any tension with the larger lines. And is this Jenny again? I think so, despite the fact that the eyes seem a bit closer and the chin a bit stronger. Could just be the raking light and the loss of one eyebrow partially hidden by the hair, plus the tighter focus. But he needs to do more than just vary Jenny's face a bit or paint her sisters. She needs to allow him to paint some other women. She's a lovely woman, admittedly, but Oxborough could stand to cast his net a bit more widely in search of a range of expressions, personalities, and heart-rending countenances. If he does this (and quits lopping off lovely limbs) someday soon he will create a large work that is as completely successful at 72” as Gondolas is at 8”.

Another painting that seems to move in the right direction is Repose in Black and Silver, an anomalous work from 2000 that Oxborough probably considers a failure. Technically it isn’t quite up to his latest standards maybe, but it actually strives for a strong mood. It has something of Whistler in it, I think, and it has a refreshing oddity about it. A more courageous Oxborough would allow himself more experiments like this, although I expect the directors at Ettinger will advise against it.

I have seen only one nude from Oxborough, six years ago, and it was very tenuous. This is certainly an untapped vein for him, although I again suspect that his galleries (and wife, maybe) are shooing him from it for reasons of their own. I will point out to him that he won’t have to compete with Gerhartz there. At Ettinger, only Steve Huston and Malcolm Liepke are doing nudes, and there is a large gap there. I don’t see Oxborough treading on either territory too much. Huston is doing faceless females with big booties and Liepke is doing the light art-deco thing.

The competition is fierce among realists in NYC, and yet, amazingly, the number of things that the artists are not doing greatly exceeds the things they are doing. As in the Santa Fe galleries in the 80’s there is a flocking and a congestion. One artist finds a lucrative niche, and a hundred others suddenly sidle in that direction. A year later the flock moves away in another direction, honking and flapping. Ettinger has become the new Grand Central Gallery, and the artists are starting to inbreed again. The slick product is re-emerging and it is being streamlined for maximum sales.

And the media is beginning to abet this streamlining. As would be expected of the modern media, it does not take part as a conscious player, it is only a mouthpiece for business. In the CNN interview, we not only get to hear from the VP of the gallery (who of course is an impartial judge) we get to hear from rich clients, who have just bought themselves a mention in the paper—something their foray into art seems to have been chosen to achieve. We are told that Oxborough is being added to a collection that includes Jasper Johns, Lichtenstein and Picasso. The buyer says, "That's exactly what draws me to his work—that kind of talent." I’m sorry, what? What exactly do Johns and Lichtenstein have in common with Oxborough? The quote works as a tip-off to the precise level of artistic understanding of buyer and writer, which is zero. It is questionable whether Johns and Lichtenstein have any artistic talent at all, but if they do it is obviously not the kind of talent that Oxborough has.

None of this rubbish is Oxborough’s fault, of course. He can hardly refuse to sell to people who own green targets and giant dot-cartoons (although I would). He has no control over stories hired out by the gallery. But he does have some control, one hopes, over who he paints. Does he really respect Chuck Close or is he just linking himself to famous people?* For myself, I don’t see the bloodline. It seems to me just another piece in the puzzling plan—written out beforehand—to ease the clientele over the nasty market hump between Modernism and the return to real painting. Greg Hedberg at Hirschl & Adler has led the waxing of the rails in this direction, writing at ARC about the links between Warhol and classical realism. But I have a revolutionary idea in regard to marketing realism: how about just telling the truth for once? The truth being that there is no link between Modernism and real painting. Warhol and Johns and all of “art” for the last century has been anti-art. It never hid this fact. It was never shy about it. The historical record is neither fuzzy nor old. Johns would spit on an Oxborough, which makes Oxborough’s bowing toward Johns nothing but pusillanimity, even if it is done through his gallery. And Warhol’s late kisses to realism are like Union Carbide’s small payments to Bhopal, India, or Exxon’s hosing down of the dead pelicans in Prince William Sound.

But back to the problems within realism. What the contemporary realists seem to have lost sight of in their competition to create the most edible paint is that they are ranking themselves on secondary concerns. Realism is currently in the grip of a technical obsession. This obsession has its roots in the eighties, when Richard Schmid and Ramon Kelley were the virtuosos of the moment. For a short time in the early 90’s I too was in thrall to this obsession with slippery paint and creamy pastels. But I got past it. I soon realized that technique was just a means to an end. No amount of bravura brushwork could hide the fact that your mind was a blank slate, that your paintings were nothing and less than nothing. The southwest scene, with its oily paints and oily workshops, soon lost its charm for me. Both the paintings and the artists were disposable, as has been proved in a very short time. The galleries like a quick turnover, since younger artists are easier to manipulate, and Schmid was soon driven out. He demanded some respect and got none, so he basically took early retirement and graduated to a life of medallions and quietude. Kelley also very soon hit a low ceiling, of his and the market’s own making, and is already mostly forgotten.

I could list many other names who have followed this pattern, but it is not necessary. My point is that the market does not create hierarchies anymore, it creates flashes and phenoms. It does this because it is upside down and illogical in every way. A market that values superficiality will of course skew itself toward superficial artists, who can fill the order. It is no surprise that these superficial artists have no staying power, since that is the definition of superficiality. Most buyers don’t want a powerful painting on the wall, especially in the conservative realist market, since that might lopside the room. They want a nearly anonymous piece of decoration, one that will blend in with the furnishings while providing, at most, a small topic of conversation.

The superficial artists who provide these expensive topics have come to rank themselves strictly in terms of technique. They seem blind to the fact that technically naïve or even technically compromised paintings are often vastly more artistic than technically perfect ones. Perhaps the ultimate example of this is Rembrandt’s The Jewish Bride. Contemporary realists would be embarrassed to have painted it. The galleries would scorn it. It is faulty in any number of ways, as a study of line or light. But it radiates tenderness and honesty. Tenderness and honesty are artistic ends. Brushwork and color and drawing are artistic means. And this is why Rembrandt is great and the superficial artists are superficial.

The figures of Corot or Chardin are another example. Although naïve and clunky by the standards of Sargent or Oxborough, these figures somehow break your heart. The artist’s technique, although not refined, is completely transparent to his intention and his emotion. This is what artistic content is. This is what painting figures is about.

As a further example, I will remind you of my commentary on the ARC Salon last year. I still like Scott Burdick’s painting and Nancy Fletcher’s little charcoal nude, but the work that has most stuck in my mind, the painting with the most lasting power, has been Aron Wiesenfeld’s Girl with Bike. Based on my line of commentary here, that should have been the Best of Show, without any doubt. It was the only work in the show that did much more than sit there and glitter. Let me be clear: I don’t like it because it was bleak, I like it because it was something. I am not calling for a new ashcan school of angst and agony. I just want some honest emotional content, good or bad.

Nor am I suggesting that artists must fake a naivete or flee a refined technique. I am only saying that, whatever their technique, it must remain transparent to their intention. It cannot usurp it or overshadow it. What is more, artists must have an intention, and an emotion (one would think that this goes without saying, but it is now almost revolutionary to claim it). Leonardo had one of the most refined techniques in history, and yet he also invested that technique with emotion. How? By having the emotion, valuing it, and knowing that it must go in the painting, since it defined the painting. All real artists have known this, consciously or unconsciously.

Can artists like Oxborough achieve this just by recognizing that they lack it? I don’t know. Maybe he needs to commit a few mortal sins, live in a tent for a year, at least do some push-ups. It is hard to say. Oxborough says in his CNN interview that he is basically proud to be bourgeois, and maybe that is OK. Chardin was bourgeois. Leonardo was a bit of a flit, by all accounts, and liked his silk sheets and room service. I am not suggesting that Oxborough has to become a bohemian or read Notes from Underground or take up rugby or start wearing a hairshirt. But if we can’t feel that his wife and kids are his wife and kids in his paintings, he needs to buy a bit of a ghost somewhere. I suppose we must leave open the possibility that his best work—in the way I mean—is in his private collection and is not for sale. His intimate portraits of his family may never make it to his galleries. All I can say is, if so, it is impossible to judge him as an artist without these paintings. Based on the paintings on the market, he could use a large dose of introspection, and might consider sharing a bit with the audience, to earn his money.

In closing, I remind the world what this little review was all about. It was about showing the world that artists have more useful information concerning art for eachother, and for any possible audience, than non-artists do. I want my reviews to work as a counterweight to all the worldly advice artists get from their galleries and accountants, a counterweight to all the phony PR and propaganda and backslapping that accompanies a modern existence, a counterweight to the pressure to sell out to hackdom and to the low expectations and tepid passions of the realist market. For those whom I have offended by speaking of a fellow artist, remember that the real critics in NY and London don’t even take the time to review realist works, good, bad or otherwise. We are beneath notice. They are too busy currying favor with the man to say anything to the point. An honest opinion about anything would be insubordinate. And the realist mags haven’t got a substantive word to say either, since anything other than a big thumbs-up and a wet kiss would jeopardize someone’s sales or advertising. But from a PR standpoint, people talking about you is always good, no matter what they are saying. It means you are worth talking about. Artists talk about eachother, and if some talk in print, so what? How is that a problem? It is a problem only for the suits, who want complete control over the press. They want to hire someone to compare the young wiz to Rembrandt and to quote the vice president of sales at the gallery. Everyone else should be muzzled in the name of politeness or policy or polity.

Realism does not benefit from the critical pass it has been given. It does not benefit from the intellectual void it currently inhabits. Nor is it up to professional writers or journalists or gallery directors to fill that void. It is up to the artist themselves, who would benefit not only from rowdy café arguments, but also from serious discussions in print. The clients and galleries may want polite trysts in the window of Dean & Deluca and CNN formula interviews that say nothing, but I remind my peers that 19th century realism—which is still mostly out of our grasp—did not reinvigorate itself decade by decade in a brightly lit chrome and enamel wasteland, over corporate coffee. Look at the bios of the artists back then and compare them to the current bios. Even the most bourgeois artists like Sargent were highly eccentric compared to the franchise people we have now, huddling at the watercooler and smiling at the boss, in mortal fear of the pink slip. This malaise can only be attacked with direct action, with a strong push in the other direction. That is what this review is.

I have mixed praise and critique here in about equal measure, which is more than any of us really deserve, including me. Compared to the reviews he gets at Art Renewal and CNN and such places, Oxborough may feel stung. But he should compare his review to my review of Jasper Johns or Bruce Nauman. I am his closest friend, in a Nietzschean sense, although I suspect he will not appreciate it for years, if ever. Let me put it this way, he is one of only about two dozen American artists (that I have seen in person) worth looking at or expecting anything from in the future. If he weren’t, he wouldn’t even be worth critiquing. You can expect that my future reviews will be limited either to famous phonies, in which everything I say will be gloriously negative, or to artists who I have some hopes for, in which case I will be no harder on them than I am on myself—and probably a lot less. As an artist, I can hardly apply different standards at the easel and away from the easel.

The bottom line is that we all have more to gain from being written about by eachother than being written about, or not being written about, by a pack of phony ignoramuses. One honest word from someone who gives a damn, for whatever reasons of egoism or altruism, is worth a billion words from those who do not. We are insiders and they are outsiders, though they would have the world believe the opposite. Art is ours, not theirs. It is ours to define and argue about. It is ours to love and cuddle and terrorize. The future of art belongs firstly to those who create art, not to those who only write about it or sell it or administrate it. And it belongs to painters and sculptors, not to ersatz umbrella designers and marketclowns and gorepushers. Let the institute babies and popculture mavens and the coifed and fanged scarebags and the compu-futuro-gothmogs create their many-tiered hell, cheer-led from every big-city rag on the planet. They can call their edifice art, but it will not fool the Muses. Only the Furies will care, and the Graeae, grateful for retribution. The descent is near, and may they enjoy the ride down.

We, however, have work to do, and part of that work is avoiding being lulled to sleep. For decades we achieved peace by fixing our fingers firmly in our ears, and now we are rocked to into a fatal bliss by the low ring of the cash register. The winners become as drowsy as the losers, the latter fooled into thinking they are worthless and the former fooled to thinking they are worthy. Most give up because they haven’t made it, that is to say, and the rest give up because they have. If you’re selling well at level 5, why look at level 6? Level 6 may not be salable. By the time you reach level 7, all your galleries will have dumped you. What to do? Listen to the lullaby and convince yourself that level 5 is the peak. Who will tell you otherwise? Who will assign you what you have left undone?

No one will but other artists. We are one another’s bad conscience. The goad and the lead. We are the only possible push and pull. And the world can learn nothing about art except from us. If we don’t teach, we cannot complain of pandemic ignorance. If the blind lead the blind it is because we refuse to take their hand, refuse to call out in the darkness. In part, it is true that the world has simply chosen to follow other leaders, and that choice is its own responsibility. But our silence is our responsibility and our shame. How much have we suffered of the silence of our elders, the silence of the Wyeths and the Bravos and the Annigonis? Our elders who took the money and retreated into seclusion. If we do not write or speak, then the world will listen to someone else. It cannot be otherwise. Therefore I will write and speak. In a poorer position to be heard than Wyeth, I am yet a thousand times more qualified than the critics and other podpeople who pull on our ears from all points on the compass. The Dantos and Careys and other ivy charlatans who have spent a full century pressing urinals and excrement upon us as fascinating finds, who have dressed their own petty and pathetic phobias and freaks in poppetclothes and danced them about our heads, singing in fine falsettos. With a wave of the arms I fling these figurines to the fires and snap my fingers like a hypnotist. Awake! Awake! Awake ye audience and arrange your clothes. Pat yourself down and take note of all your limbs. You are a man, not an airy monster, and you live under the lovely Sun who expects you to be alert. Snap to! Art history is not some tasty mint to be passed from mouth to poison mouth ‘til it dissolve completely. It is not some shiny coin pulled from the ear of a nasty mime. It is not the hostage or whore of every red-nosed Stentor who owns a tattered thesaurus and a thumbscrew collection. Art history is the Bible and religion of true artists, a holy book you can read only after we have written it, a shrine you can visit only in barefeet, with your goddamned mouth shut. If you have questions, stare at the ceiling for a decade before you mail them in. Better yet, stare at the paintings and hum a little prayer to the subtle Muse. The answers are all within.

Which is to say that the journalists should be interviewing us, not the reverse. When curators lecture artists you can be sure that madness is afoot. Likewise, when galleries and clients and interior designers determine subject matter, art is set to dissolve into a misty decoration, an impression of a design of a hint of a tonal harmonic blob. In a rational world the artists would be lecturing to the galleries and curators and critics and clients. Yah, and when that happens I will be the Prince of the Alabaster Palace of Petit-Sylphs.

*I discovered the truth later, when the National Portrait Competition hit the walls in the summer of 2006. This portrait was done for that competition, and it appears that Close was chosen to appeal specifically to the jurors. You can read my comments on the NPC here.

If this paper was useful to you in any way, please consider donating a dollar (or more) to the SAVE THE ARTISTS FOUNDATION. This will allow me to continue writing these "unpublishable" things. Don't be confused by paying Melisa Smith--that is just one of my many noms de plume. If you are a Paypal user, there is no fee; so it might be worth your while to become one. Otherwise they will rob us 33 cents for each transaction.