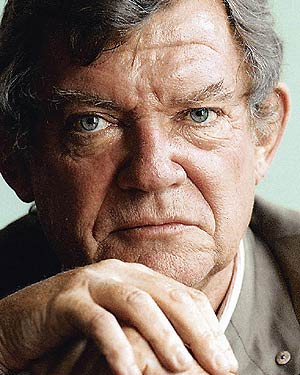

On Robert Hughes [Robert Hughes has been the art

critic for Time Magazine since 1970.

He wrote The Shock of the New—an influential overview of

Modernism—as well as many other books on art and criticism. More recently he narrated a history of art

for the BBC.] Hughes' quotational prelude to

his book Nothing if not Critical is

from Othello: Desdemona: What wouldst thou write

of me, If thou shouldst praise

me? Iago:

O gentle lady, do not put me to 't, For I am nothing if

not critical. Desdemona: Come on, assay. All right, I shall assay. And I shall start out by praising, for a

change. If you had to choose a

non-artist to be an art critic in the 20th century, it would have to be Robert Hughes. He is well-read, clever, funny,

opinionated, pugnacious, and a very good writer to boot. He has been invaluable in his role as axe

swinger in the Modern forest of deadwood.

A burly, straight-shooting Australian, Hughes is a not a welcome sight to

anyone out on a limb. He has taken the

trunk out from under many big names in art, including Karen Finley, Robert

Mapplethorpe, and Julian Schnabel. His

analysis of the current state of the avant garde is often incisive and

amusing. And much of his broader-based

criticism of American postmodern culture is spot-on. Of

course, in my opinion, one doesn't have to be an artist to critique Modern

art. Hughes is exempt, most of the

time, from my standards of responsible criticism because he is not judging art

but exposing its pretense. He really could

do what Julian Schnabel does, if he hit his head and decided he wanted

to. In some

ways Hughes has sounded the death knell of Modernism. I give him a great deal of credit for convincing many that Modern

art has finally bottomed out. I do not

believe in historical necessity, and I do believe in the great power of

the individual: if Hughes had been of the Greenbergian mold, he might have

propelled Modernism to even greater levels of falseness and insolence on his

personal powers of persuasion alone.

Instead Hughes has been arguing so loudly and so well that the

stagnation of art is upon us, he has made some aware this fact at last

(without, however, realizing how overdue such notice is.) He has seen the writing on the wall, has all

but screamed that "art is dead"—but he can't seem to feel good about

it. There is nothing, in his mind, to

fill the gap. Fortunately there is

a gap that needs filling for him, and that, if nothing else, sets him apart. Despite all this I have always

felt that on the whole, and at the most critical times, Hughes is a man

"lost in his neighbor's fields" (as Whistler said of Ruskin). His cynicism surrounds and dismisses not

only the dying gasps of Modernism, but often the viability of visual art itself. In one lecture we find him, for example, damning

art because "What really changes political opinion is events, argument,

press photographs, and TV." Or

claiming that art is not "morally ennobling" or even

"therapeutic" because it does not have an effect on everyone who

comes in contact with it. But this is like saying that because some boats sink, water

is not bouyant. And judging art

politically is simply to misjudge it, as he seems to understand at other times. For instance, he says in the very same

lecture ["Art and the Therapeutic Fallacy," The

Culture of Complaint ]: Likewise, museum people

serve not only the public but the artist...by a scrupulous adherence to high

artistic and intellectual standards.

This discipline is not quantifiable, but it is or should be

disinterested, and there are two sure ways to wreck it. One is to let the art market dictate its

values to the museum. The other is to

convert it into an arena for battles that have to be fought—but fought in the

sphere of politics. Only if it resists

both can the museum continue with its task of helping us discover a great but

always partially lost civilization: our own. And so he answers his own

question about changing political opinion: it is not the place of art to be so

worldly. A political opinion is mainly

analytical—an opinion on expediency or short-term viability—and therefore

cannot be an artistic statement. In this

sense, politics

may be thought of as the argument that determines the current structure. But art is part of the substructure. Hughes proves this in the next to the last

paragraph of the lecture, where he gives a striking account of his reaction, as

a woodworker himself, to seeing the great Japanese temple of Horyu-ji:

"...resentment? Absolutely

not. Reverence and pleasure, more

like." Did he take away points

because the temple had no message, made no statement, had no clear political, intellectual

or linguistic undertones? I doubt

it. In

fact, I know he didn't, for in a review of Chardin he says, "To see

Chardin's work en masse, in the midst of a period stuffed with every

kind of jerky innovation, narcissistic blurting and trashy 'relevance', is to

be reminded that lucidity, deliberation, probity and calm are still the chief

virtues of the art of painting." Of course they are, and only when Hughes

is judging contemporary art does he forget this. For any contemporary art, almost any 20th century art, fails

miserably when held to these standards.

In the second lecture in The

Culture of Complaint, "Multi-Culti and Its Discontents," Hughes

again proves he knows what art is for.

He quotes a fellow Aussie, Andrew Riemer, who sees that

The literature of

England [Tennyson, Keats, Shelley] conducted us into the world of the romantic

imagination which served one of the essential needs of adolescence. It also catered generously for others: a

heroic or noble past in which we could participate, and ethical structures to

provide models for fantasies, if not for actual life. Hughes does not take exception

to this view. The only thing to be added to such a concise statement is that

surely the needs of the imagination do not die with adolescence. We will always need, both as individuals and

as a society, a source for such spiritual replenishment. Still,

Hughes is apt to forget this. He mentions

William James' account of a trip to the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in

Boston with little reverence: "Visiting such a place, he [James] wrote,

would give harried self-conscious Americans the chance to forget themselves, to

become like children again, immersed in wonder." But Hughes begins the next paragraph with a sneer: "The idea

that publicly accessible art would help dispel social resentment lay close to

the heart of the American museum enterprise." As if "forgetting themselves" and

"dispelling social resentment" are strictly equivalent. Here Hughes has fallen into the modern trap

of seeing all pleasure as politically regressive. He implies that classical art is simply or predominately an

opiate. It does not follow, however,

that children, or adults like children, immersed in wonder, would have

their social resentment dispelled by such an encounter with art. I believe it more likely that a positive

encounter with art causes social resentment. For why, a visitor will think, should such moments of purity and

wonder be available only in museums?

Why, if such visions of beauty, peace, or emotional honesty are

imaginable, are paintable, are they not liveable? Despite his aggression toward

certain contemporary artists, Hughes has come down on the side of the Moderns

in their redefinition of art as theory and politics. The Shock of the New, his most influential book, is

both panegyric and apologia for Modernism. He certainly never takes the big names in the book to task for

anything. He rarely applies the same

standards to the early stars of Modernism that he applies later to the lesser

stars of PoMo. We get more myth-making

than we do criticism. He is clearly not

interested in attacking Modernism as a whole.

Although Hughes sometimes shows traditional tendecies, he never

sides with classical writers. He would

never agree with Hesiod, for instance, who said, "The Muses were born that

they might be a forgetfulness of evils and a truce from all cares." Or with Schiller, who said, "All art is

dedicated to Joy." These

sentiments are clearly pre-Modern and passe, and no one who even knew of them,

much less mentioned them in print, could have hoped to have been hired by any

magazine in 1970, or accepted by a major publisher. No, the opinions of pre-Modern artists and

writers are never seriously addressed by Hughes, or anyone else, except in the

case they can be given a spin in the direction of Modernism. Whistler is misrepresented as being a

pre-formalist, for example, but what he actually said about art is never

mentioned. Nor is Matthew Arnold, one

of my favorite writers, who said this, Tragic art has failed

when a state of mental distress is prolonged, unrelieved by hope; in which

there is everything to be endured, nothing to be done. In such situations there is inevitably

something morbid, in the description of them something monotonous. When they occur in actual life, they are

painful, not tragic; the representation of them in art is also painful. Hughes would never mention it

since clearly this one quote undercuts the entire Modern argument for its

"shocking" choice of subject matter, and completely dissipates the

"shock of the new." According

to Hughes, the shock of contemporary art is meant to educate—at least to the

extent that propaganda can educate. But

not even propaganda can successfully propel by causing pain alone. Brutality and vulgarity, shock and horror,

can educate and propel only in the way that tragedy has done, in the way that

Arnold implies—that is, by artistically resolving the pain it causes. Modernism has attempted to divorce the

subject matter of tragedy from its artistic context and forms. It causes visual or emotional or

psychological pain without giving a clue to its end. In this way it has become an unwitting accomplice to the

oppressor it claims to oppose—whether that oppressor is Nature or the Gods,

in the case of classical tragedy, or some social flaw, in the case of

contemporary theory. It does not

resolve pain, it only adds pain to pain.

It does not educate through horror; it only horrifies further. If this paper was useful to you in any way, please consider donating a dollar (or more) to the SAVE THE ARTISTS FOUNDATION. This will allow me to continue writing these "unpublishable" things. Don't be confused by paying Melisa Smith--that is just one of my many noms de plume. If you are a Paypal user, there is no fee; so it might be worth your while to become one. Otherwise they will rob us 33 cents for each transaction. |