return to homepage MoMA and Dada

return to 2004

how to spend a Billion and

get nothing but new Stairs

by Miles Mathis

The Museum of Modern Art in New York City is one of the most important institutions of Modernism in the world. For decades it has propped up Modern theory by exhibiting trivialities and nullities as pieces of serious culture. It, along with the Whitney Museum and the Guggenheim, has made New York the world capital of Modernism, showing the way for such spin-offs as the Pompidou Center in Paris, the Guggenheim in Bilbao and the Tate Modern in London.

MOMA recently moved into a new building, precipitating a fresh round of articles in the world press. I suspect that such moves are made mainly for this purpose. Since these Modern museums are trumped-up spectacles from the beginning, there is little for the media to report on except the occasional new building. The Museum in Bilbao is the perfect example of this. Without Frank Gehry’s absurd building there would be nothing to comment on except ugly rooms of tinker toys and airplane wreckage. The same can be said of the Pompidou, which most visitors treat not as a museum but as a circus ride or a house of mirrors at the fair—a place to giggle and make faces.

The truth is that the Modern or Contemporary Museum has much more to do with architecture than with art. The original Guggenheim began this trend with its Frank Lloyd Wright “headless Michelin Man” design. [I have always thought that the Guggenheim would make more money if it rented rollerblades at the top and piped in pop music. The walls could be re-covered daily in canvas, the skaters could be given brushes, and they could paint masterpieces as they raced eachother to the ground floor.] No one but the most nebbish and deluded pseudo-intellectuals goes to such places to look at art. All the “art” could be taken down and replaced by Hefty bags and no one would know the difference. This is made clear whenever a second-level city like Austin or San Diego or Denver builds or thinks of building a new museum. No consideration is given to what collection the museum may house, since this is beside the point. All public and private debate is centered on the architect to hire and how to fit the promotional package around the new building.

The entire explanation for the continued existence of the Modern museums is the steady stream of propaganda that the media puts forth on the topic, and that propaganda is always heavy with kudos to the architects and chairmen and corporate sponsors. The writers of such pieces seem to understand that there is no art to report on, and that describing the possible content of the museum is counterproductive on every level. The press release is a sample of public relations, and to court the public it is best not to annoy it beforehand with papier-mache turds and piles of rocks. That can come later, once the funding has passed. At the beginning, all the public needs to know is that tourists will arrive, spending money and buying film and creating jobs so that babies may be fed and cars filled with gas (or the reverse).

For some reason which remains a mystery to me, nearly every mainstream publication feels it necessary to publish a squib from the avant garde on a semi-regular basis. Even the Wall Street Journal, which no one would accuse of having leftist tendencies, has for a long time reported on the avant garde, usually taking reports straight from the horse’s mouth (or the reverse). Time and Newsweek have also played pony for Modernism, although there is no chance that even a small minority of their readers is really interested in what Bruce Nauman or Cindy Sherman is up to. Reports on contemporary art would seem to fall somewhere between reports on Hollywood celebrities—which, though vacuous, really do seem to interest a lot of people—and reports on books and operas—which, though beyond the experience of most readers, are considered edifying. What is never explained is how Nauman sitting in a room in clown face is supposed to be edifying. Modernism has somehow continued to ride a cultural wave without ever having to justify its presence on any grounds. It does not satisfy on the level of kitsch, since no one is showing cleavage or getting married or divorced or dating Jennifer Aniston or telling jokes or sword fighting. And it does not satisfy on the level of art, since it consciously, explicitly, and with great fanfare gave up on that long long ago. The only answer seems to be that people are making a lot of money. Nauman is very rich, and that in itself is fascinating to the public. I suggest that it therefore makes more sense to put the articles about Modernism in with the articles about lottery winners. They have achieved their notoriety with equal amounts of skill and worthiness.

What MOMA has done that many of the other Contemporary museums have not is leaven their collection with a few actual works of art. MOMA’s status and longevity have allowed it to collect several works which bring real people through the doors for real reasons. Van Gogh’s Starry Night is foremost among these. But I am here to bury Caesar not to praise him. I am fairly certain that were Van Gogh’s ghost able to speak, he would tell us to please move him to the Met where he belongs, not here among all this fakery.

Those who want to read glowing reviews can be satisfied almost everywhere they turn; you must think of this article as the counterpoint to the Chamber of Commerce-approved opinion. For I have always found MOMA to be one of the most annoying places on earth. This should come as no surprise, since from its initial charter MOMA’s founding principle and raison d’etre has been to annoy people like me. The overriding aim of Modernism has always been to foil any natural desire for art. To weed it out, to chastise it, to mock it, and finally to extirpate it. Those like me who resisted this surgery, who did not go gentle into that good night, have been treated as atavisms—as the vestigial tails of art, refusing to be lopped.

One of the greatest unrecognized facts of recent history is that the artist was the first enemy of Modern art. He is still its greatest enemy. His presence is what kept art from being completely monetized for centuries, and his continued existence is the one true danger to the current market. Every dollar and every drop of ink is therefore ultimately spent and spilled to annoy, deflate, alienate, and finally destroy every last artistic impulse in every last artist. Once this is achieved, the father and god will have been killed, and the children will be free forever.

Many or most will not understand what I mean by this, I know. I may seem to be taking it all a tad personally. To show you why I am justified in these feelings, it is best to go to the works of the Moderns themselves. So that no one may accuse me of selective editing, I will take all of the examples below from MOMA’s own “highlights” reel, as chosen by its curators for the website.

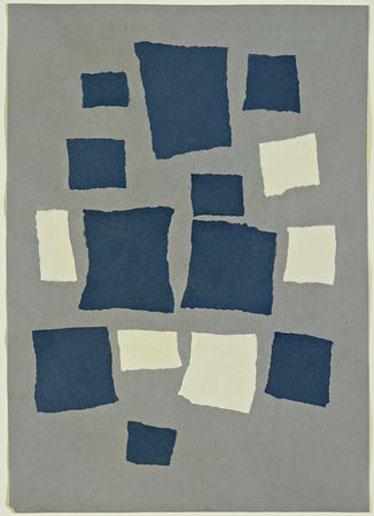

I will start with Jean Arp’s Chance Collage, a very famous work that any student of art history would recognize. It is just a handful of square paper scraps in a frame. This is a very early, very successful sharp stick in the artist’s eye. It says to me, “Once this has been accepted as art, all skill, ambition, beauty, meaning and subtlety are right out the window.” What is more, it was intended to say that. There is no other possible reason for its existence. No one could find it interesting for any other reason. Does anyone imagine that Arp actually found this assemblage poignant in any way? We can only feel pity for anyone who would look at this work and be aesthetically challenged. It is clear that the work is important because it is one of the most successful gauntlets thrown down to the artist. It works as a semi-powerful nullity. Its reach is defined by what it destroys. All of Modernism is finally judged in these terms.

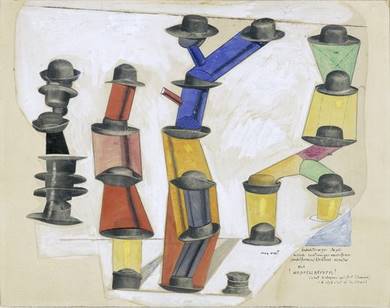

Max Ernst’s The Hat Makes the Man is another very clear example. There is nothing here that could be mistaken for aesthetics. Warhol’s Where’s Your Rupture is basically just a reworking of this nullity, where a stupid advertisement stands as the artist’s entry in the most meaningless thing imaginable category. Why seek the most meaningless thing imaginable? To take the most wind out of those who seek meaning. Ernst says, “I am rich and famous and happy and clever by giving the world works like this. Why then seek meaning and beauty and depth? Your only reward will be a severed ear or abuse from the burghers.”

A more recent entry in this game is Frank Gehry’s Bubbles Chaise Lounge, a pseudo-sofa made by folding a large piece of corrugated cardboard. This would be clever in a 7th grade show and tell. In a museum it can only be understood as kick at the artist. In 7th grade, it would not have pre-empted high achievement. In MOMA, it does.

Jenny Holzer’s intent may not have been as destructive as Gehry’s, but her Truisms, a list of very uninteresting clichés, pre-empts real art just as successfully. Truisms appropriate level of publication and payment I would put at Parade Magazine and $100. The idea is just that clever. Instead she has found space and fame through the top Contemporary museum in the country.

Similar in appeal and complexity is Lorna Simpson’s Wigs, a collection of wigs worn by African American women. This would be a proper display at a cultural center, where it was treated as a cultural selection, not as a work of art. It would go up for a week or two, generate small interest (since it is something that can already be seen on the street) and then disappear. Here it is offered to the audience as much more than that. Simpson becomes an artist, a person with vision. No doubt we will soon see a wig in the shape of an Absolut bottle.

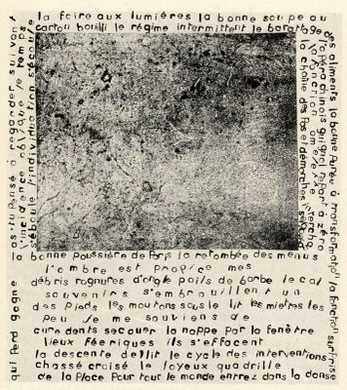

Jean Dubuffet’s La Lunette Farcie returns us to the old school of nullities, where artists actually spent a good deal of time constructing nothings. Here we have a “farcical” book—a collection of random words and completely accidental images that poses as a book. Unfortunately, it stands mainly as another proof that the Moderns have never understood the meaning of “farce.” A farce is supposed to be a humorous absurdity, but the avant garde has so far delivered on only half that promise. La Lunette Farcie, like every other proposed farce of Modernism, fails to produce even the slightest grin. The only successfully humorous works of Modernism I have seen are works that were meant to be taken very seriously, like Picasso’s Guernica. I laughed out loud in front of Guernica, to the astonishment of the room. Guernica is true farce: comically drawn figures trying to express the horrors of a mock bullfight—which is supposed to stand for the much greater horror of civil war. This is a rich absurdity, all the more so because it was, we must suppose, unintended. [Of course I know that speaking honestly about Guernica is seen as anti-social, maybe even suicidal. Drawing a mustache on the Mona Lisa is subversive. Subverting Guernica is forbidden. Subvert all tradition but our own, says Modernism.]

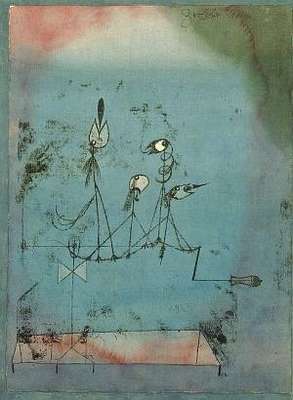

I am unsure whether Paul Klee’s Twittering Machine is meant to be farce or nullity: it sits on the fence, almost being funny, almost being something. The only thing I like is the title, which is undeniably cute. The painting itself I don’t get a twitter or a twitch from. It is a mostly banal design, indistinguishable from many another sofa cushion pattern or bath towel.

In the same vein we have Joan Miro’s The Birth of the World, which is the birth of nothing but a few inconsequential shapes. A more poignant title might have been The Birth of a Bad Haircut. Likewise for Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie. It could have been titled The Empire Bagged a Wookie and no one would have been the wiser.

Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel shows off his incomparable ability to annoy the artist. Duchamp may be the single most influential figure in Modern art, due to his early recognition of the pattern. Why waste time subtracting this and that from the conventions of art? Why not do away with it altogether as an historical nuisance? The only problem with this is that he never understood the basic usefulness of an endless pointless variation of nothings. The only thing that is more annoying to the artist than non-art is the successful proliferation of non-art. In this and only this was Duchamp outdone by Warhol.

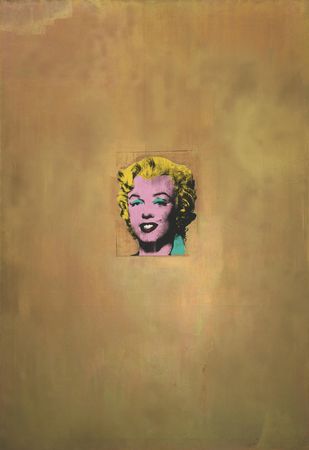

Warhol’s Gold Marilyn, like his other most famous works, was not only a nothing, it was an easily reproducible nothing. Warhol’s genius was in choosing meaningless objects that were already ubiquitous, so that the equation worked both ways. The everyday object became art and the art became everyday object. It was therefore in plain sight at all times, eating away at the artistic spirit, annoying the artist from every direction. No longer could the artist hide, refuse to go to the museum, refuse to read the review, refuse to buy the book. No, the reminder was now everywhere. The cereal box, the can of soup, the washing powder—all of them became daggers, cutting artists everywhere. We bled from a thousand wounds, were infected by bugs of a million varieties. The very possibility of art became an impossibility. The legacy of Andy Warhol.

Louise Bourgeois benefited from this legacy, since she was never artist. Her entry in the highlights reel is Articulated Lair, a series of steel and rubber partitions that look like the changing rooms at Anne Taylor. This is what she had to say of it, “It’s a protected place you can enter to take refuge.” Maybe Louise felt protected surrounded by polished metal and rubber, but I would not. I might just as soon go for a sojourn at the airport lavatory, seeking spiritual comfort.

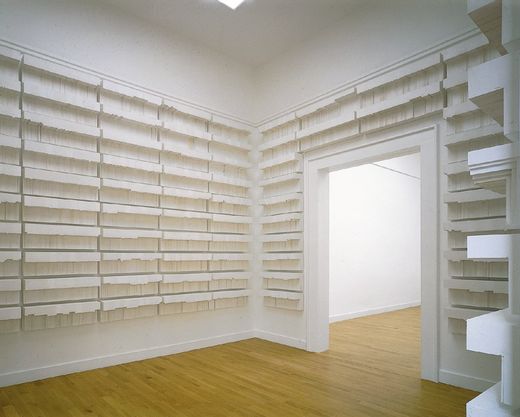

In this spirit of meaningless installations is Rachel Whiteread’s Paperbacks, a room full of empty shelves pressed in white plaster. Rachel is obviously still smarting from that honorable mention in the junior high science fair (along with Damien Hirst) and she is determined to force her mediocre ideas on us until we re-invite her to the prom. She is the one, I believe, who once took a mold of the empty space underneath a chair. . . and got famous for it. One begins to wonder how the artists who didn’t make the highlight reel must feel, being beaten out by someone who came up with the idea of sculpting negative space. It must be crushing to realize that your idea of nothing is inferior to someone else’s idea of nothing. At least Warhol and Duchamp could preen themselves on the idea that they won the anti-talent show. How discouraging it must be to find that your no-talent is 9th place or 23rd place in the list of no-talents. “I can’t even lose properly,” you would say to yourself.

Late in its career, MOMA discovered that it didn’t even need to bother with buying things that posed as works of art. It could just exhibit ball bearings and coffee tables and Sony TV’s and Pillola Lamps and save itself a lot of time and money. It was thought then that the Modern artist had finally finessed himself into obsolescence. Why pay a million dollars for a picture of a can of soup when one could be got for 79 cents? Why exhibit paintings of ballpens when real ballpens could be exhibited much more efficiently? Besides, the public as well as the curators could see that a design for a Jeep or a Swatch watch took some skill. Here at least were artifacts that were not absolute mockeries and absurdities. But, although these exhibits were popular, they did not stay at the heart of the Modern enterprise, which was to undercut all skill and meaning. This required real non-artistic intent, which required real non-artists. Designers were simply too close to artisans for comfort. MOMA has kept its ballpens as a sort of niggling annoyance to the high-minded everywhere. But the consensus was and still is that manufactured pieces of garbage like Nauman’s FACE MASK must remain central to the museum’s message. No real cultural artifact, taken from a real market, can hope to be as theoretically debilitating to the artist’s psyche as an obscenely rich poseur. Fake artworks are not nearly as annoying when they are separated from fake careers and fake people.

I believe I could comment negatively on every entry in every category. Except for Starry Night, MOMA has a nearly flawless record of gravitating to bad work. Even the most popular pieces—a majority of which are technically pre-Modern—are vastly overrated. Degas’ At the Milliners is not one of his best works, nor is Klimt’s Hope II, nor is Rodin’s Balzac. Balzac is a piece of sculptural laziness by a famous old man who was by then more interested in sketching the little kittens in embrace.

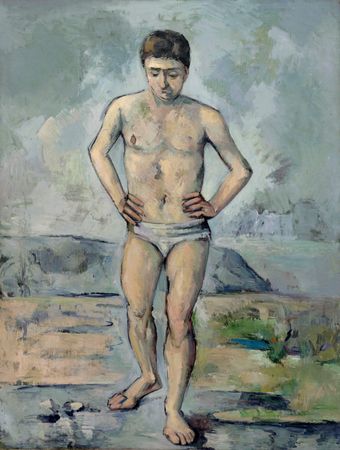

Cezanne’s The Bather is further proof that the artist should have stuck to fruit. Dali’s The Persistence of Memory is little more than a cheap gag.

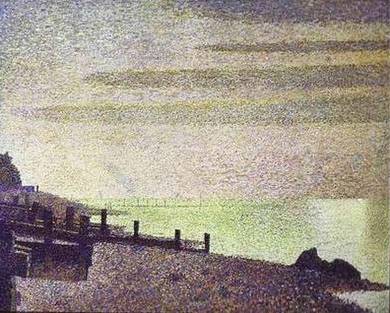

Seurat’s Evening, Honfleur has always impressed me as the highest achievement of his mechanized technique, a technique that led inexorably to the paint-by-numbers kit. In my mind, that airport lavatory where Louise Bourgeois huddles for spiritual consolation has a print of Evening, Honfleur next to the condom dispenser. The critics of the avant garde always have a field day comparing 19th century academicism to coffee can and tobacco tin art. But what could be more representative of the soulless mall shop poster than any painting by Seurat? Dali is a half-step up from this, decorating that cubicle space next to the fridge at the office, where half-drugged dayworkers can examine the philosophical conundrum represented by a rubber watch. These are the same people who find Star Trek Voyager plots richly textured and are convinced that M.C. Escher has discovered the road to paradise with upside down stairs and hands that draw themselves.

If you want to see real art, you will have to go to the Metropolitan or the Frick. So as not to seem to be a complete grumpus, I will close by recommending the works in New York City that I truly love.

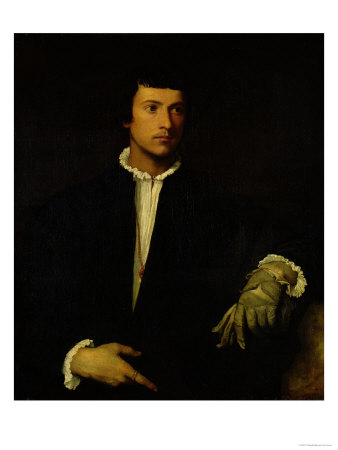

First among these is Titian’s Man in a Red Cap, at the Frick. Along with his Man with a Glove in Paris, this stands as one of the finest portraits ever painted. It is a miracle of coloring and shading. It is also a technical marvel, the paint layers not having suffered diminution in almost 500 years. Van Dyck’s portraits at the Frick are equally fine. Several of Corot’s landscapes owned by the Frick are among his greatest. At the Metropolitan is a marble head that most pass by.

It is Head of an Athlete, supposedly a Roman copy of a Greek original from the 5th century BC. It is one of the most beautiful heads ever sculpted. Sargent’s Gitana is also very strong, overpowering his larger works there. Carpeaux’s large marble group Ugolino and his Sons sits almost on top of the coffee shop at the rear of the building. Squeeze in behind the espresso machine and look at the younger children. Both the Frick and the Metropolitan have some very fine Rembrandts, the best of which may be the self-portrait at the Frick. And finally, I always visit the glass cases downstairs at the Metropolitan where less famous works are stored. In the sculpture cases are several astonishingly beautiful works in bronze and marble, by various artists. The works are only numbered, and I never remember to write down the names from the computer searches. But two or three among them deserve to find a place in the atrium, with large plaques announcing their proud creators. Almost any work in the case would be worth the entire Museum of Modern Art.

If this paper was useful to you in any way, please consider donating a dollar (or more) to the SAVE THE ARTISTS FOUNDATION. This will allow me to continue writing these "unpublishable" things. Don't be confused by paying Melisa Smith--that is just one of my many noms de plume. If you are a Paypal user, there is no fee; so it might be worth your while to become one. Otherwise they will rob us 33 cents for each transaction.