|

return

to homepage

return

to updates

Currin

Again

by

Miles Mathis

go

to first Currin article from 2004.

go

to second Currin article from 2004.

I am but mad

north by northwest:

when the wind is southerly, I know

a

hawk from a handsaw.—Shakespeare

February

13, 2008

In this latest winter of our

discontent, the desperation of the New York avant garde is

reaching new and perhaps final levels of gassiness. Realizing

that they once again, for the 92nd year in row, have

nothing to write about or look at worth writing about or looking

at, they return, as if by rote, to John Currin, their last best,

though pathetically shallow, hope. One can only hope, with pathos

and bathos, it is their last.

Now, Currin himself admitted going

into a funk—or what he called a “dry spell”—in 2004,

after his success at the Whitney and all his big-city write-ups.

It wasn’t very good timing for a dry spell, since Gagosian had

just taken him away from Andrea Rosen and raised his prices into

the exosphere. Two years later, in 2006, Currin had a small show

at Gagosian which did not even come close to selling out. Many of

the paintings are still listed at the Gagosian website. Beyond

that, none of his works since 2003 are nearly as interesting—even

as illustration—as his earlier things like Hobo and

Sno-bo. He has developed a heightened interest in

technique, as we shall see, and his technique has gotten a bit

better in the meantime. But it appears that he has long since

emptied his narrow quiver.

Not to worry, the avant garde has

never needed actual artworks to go on. It subsists entirely on

the write-ups and always has, and if breasts are sagging or

members are flagging, they just spill more ink in more high-tone

places. Hence we find another long pointless paean in the New

Yorker , to follow similar things in GQ and Penthouse

and lord knows where else. A small, sad show in London is the

proffered occasion this time, but that is just an excuse for

another blubbering tour through the fashionable townhouse and a

rehash of the resume.

The readers and writers of

contemporary magazines—these Leviathans of taste and

culture—don’t know art from garfunkel, but they hunger for

pictures of the artist and his family and his bed and his studio

and his wine cellar and his bookshelf and his palm pilot and his

tie collection. And they thirst for gossip about his past and his

future and his prices and his dog and his childhood sweethearts

and his suits. To them it matters not what Currin has or has not

painted, it only matters who he has married and what parties he

goes to and whether he is the 19th best dressed man on

the East Coast or the 20th, and how tall he is.

I would have been too shagged out

from chronic malaise to comment on this, except that Currin says

a couple of exceedingly stupid things here, even stupider than

usual (even stupider than the avant garde artist is usually paid

to say) and this put me in the mood to write.

As it turns out, Currin is now so

desperate for relevance that he is trying to tie his recent

pornographic output to world politics. Let me lead by saying I

don’t care that he is painting porn. It doesn’t offend me; it

doesn’t impress me. I look at nudity and sex on the internet

and sometimes enjoy it. The difference is I would never try to

defend my art, or apologize for my sex-gazing, by tying it to

politics of any kind. But for some reason Currin finds this

necessary. He says,

I know how right wing this sounds .

. . but I was thinking how pornography could be a superstitious

offering to the gods of a dying race.

No, John, that doesn’t sound

right wing, it just sounds phony. It is the among the

worst-disguised fake philosophy of the last decade (and has a lot

of competition in that regard). And it doesn’t even make sense.

As far as this “dying race” is the race of people with white

European ancestry (this must be what he means, in context), the

gods of this race would not and could not be propitiated by such

an offering. If this race is dying then it is dying because its

gods are Mammon and Moloch, not Isis or Aphrodite or Freyja. Our

gods are not big-dicked totems or cow-uddered rock carvings and

haven’t been for millennia. Those gods are buried deep in the

earth and you couldn’t raise them by a century of sex or a pile

of porn to the moon.

Currin can’t really think he is

being superstitious or religious, but even if he did he would be

very confused. A chrome and enamel flat in Soho is not the first

place one would think to go to build a pagan altar to the earthy

gods. If Currin is trying to score points in some heaven, his

checks from Sadie Coles and Gagosian and his deification by

Robert Rosenblum and Peter Schjeldahl are not going to be

outweighed on the scales by a million hecatombs of burning oxen

or by a billion beddings of Erato.

And they especially are not going

to be outweighed by such tepid and ugly images as the new porn

series. Sno-bo was a thousand times sexier than these new

copulation shots (and even she is not going to score high with

the Muses—as I have it from them directly). Of all the porn to

pick, why this?

Currin tells us he painted this

because of the twelve Danish newspaper cartoons of the Prophet

Muhammad and “the killing of Theo van Gogh, the film director,

by some jihadist in Amsterdam—all of a sudden the most liberal

societies in the world were having intimidation murders happen.

That's when it occured to me that we might lose this thing—not

the Iraq war but the larger struggle.”

As if that weren’t enough and

more than enough, he continued,

I'm gonna have a fucking fatwa on

me for saying this, but I had a kind of cockamamy political idea

that this is what we're fighting the Islamists with: They've got

the Koran, and we've got the best porn ever made! I mean that as

a joke but also as something that's literally true. . . .In the

European theater the question seemed to be, “Who's going to

win? Allah or porn?” Personally, I hope we win. I hope porn

wins.

Didn’t Currin have some sort of

veto clause in this interview? Some sort of emergency small-print

that allowed him a late self-edit just in case he started quoting

Rush Limbaugh or started channeling Danny Bonaduce from the

Partridge Family, Season 2? I mean, good god, what

is this about a “European theater”? Does he mean the cineplex

in Hamburg, or is he leaning over a map in his basement, moving

around toy soldiers and Sherman tanks?

Just to be clear, these quotes

don’t sound either left or right to me. They sound like Currin

has been scouted by the CIA, and the CIA is (officially)

non-partisan. Currin lives in NYC and has eyes and ears. Almost

seven years after 911, he can’t really believe that the Muslims

are the enemy in any real “theater”, or that Islam is the

primary threat to world peace. No, his “dying race” is that

threat, and everyone knows it, or should. Outside the US, this

knowledge is nearly unanimous. I just lived in Belgium for three

years, and I can tell you that white Europeans, even the ones who

want the Muslims to live somewhere else, don’t think any nation

of Islam is the primary aggressor in the world. The Dutch and

Flemish nationalists may want uni-culturalism above all else, but

unless they are also with covert operations—like Theo van Gogh

was (is)—they aren’t denying that the US is the empire on the

move. Europeans have their own sort of blindered and blinkered

view: they no longer see themselves as the problem—since we in

the US have taken on that mantle. In their eyes, they are not the

dying race, we are. Like the Native Americans, the

Europeans are waiting for us to commit cultural suicide, so that

they can pick up the pieces. We may be the great great

grandchildren to these Europeans, but we left the house long ago.

We aren’t their concern anymore. They can deny the blood link,

if it comes down to it. In their opinion, we are committing

cultural suicide by spreading empire too far, too fast, and with

no finesse. They know that in the tally of “intimidation

murders” we have no competitors, in this century or any other.

We left the Huns and the Romans behind us decades ago. Even the

Germans look at us like a newly minted race, capable of things

even they never thought of.

But it should not be necessary to

live abroad to have some inkling of this. I hear that the

internet may now be available in Manhattan. Currin is sold as

avant, cutting edge, smart-as-a-whip, Yale-educated, Jewish

married, and so on; but he still gets his news straight from the

White House or Rupert Murdoch, apparently. This doesn’t make

him rightist, necessarily; it makes him either an idiot or a

plant.

We will assume he is not an idiot.

We will assume that he is using words like “cockamamy” only

to seem like a friendly rube, appealing to the common man that

reads the New Yorker. But that begs the question if he is

getting his politics from his in-laws. All this talk of Theo van

Gogh and Islamic jihadists and so on sounds an awful lot like

Alan Dershowitz. I don’t think Dershowitz has ever pulled porn

into the mix like this, but otherwise the similarities are

striking. The hawks, Jewish and non-Jewish, always find a way to

focus on the one guy in Holland instead of the thousands or

millions with our mark on them.

Like his handlers—whoever they

are—John has to pretend to be more concerned with one or two

“intimidation murders” in “liberal societies” than he is

with millions of murders in Iraq and around the world. For him,

the question is not Iraq, it is the “larger struggle” of porn

against Allah.

This can only be seen as a perverse

new twist in the globalist bi-partisan Jewish/Christian/Atheist

propaganda machine to sell pre-emptive and continuous war as “a

guarantee of freedom.” We are not murdering innocent men,

women, and children just for oil, we are doing it for porn.

Well, John, that really sells it

for me, boy. I had thought we were doing it for some selfish

reasons—so that we could continue to drive our Hummers, for

instance, and talk on our cellphones and drink bottled water. But

no, it is so that we can continue to masturbate with full rights

and a clean conscience. The fertility gods must smile upon such

actions. What do they care if hundreds of thousands of foreigners

conceived in sex are starved and killed in forests of famine and

lakes of blood, as long as we follow it by a Soho sacrifice to

Frigg? One or two shitty paintings should buy us a quick

indulgence, a guarantee of a touchdown or two, and a convincing

win in the war for “democracy.”

Do I expect anyone else will call

him on this, especially from the so-called left? Not a chance. In

the “American theater”, there is no left, at least not in the

art scene or in the journals. The progressivism of the avant

garde is just a pose, a marketing ploy. When it gets right down

to it, these people have all the creative courage of a Hallmark

Card or a member of Congress.

In championing any kind of freedom,

even the freedom to masturbate, Currin will be hailed as a hero

of the left. Worldwide mass murders don’t register with these

people. Republican and Democrat, Jew and Gentile, they hold hands

and sing God Bless America while robbing the poor box to buy more

bombs. Even 3000 of their own murdered, in their own home town,

by their own government, can be ignored as inconsequential next

to the freedom to masturbate and make false offerings to silly

gods. Some radical feminist at the Village Voice can

attack Currin for painting big tits, that is, but don’t expect

anyone to attack him for parroting CIA handbills or for sounding

like a commercial for the Department of Defense. The

Pentagon-Porn alliance: “Fighting Terrorists, one Fuck at a

Time!”

But let’s switch gears and

actually look at the paintings. I know this will shock the avant

garde: actually having to look at the images without a pre-set

screen, a playbook, or a list of platitudes. But it occurs to me

it might be helpful.

Here is what Currin says about

them:

I’ve always felt insecure about

being a figurative artist, and about being an American painter.

My technique is in no way comparable to that of a mid-level

European painter of the 19th century. They had way

more ability and technical assurance.

As I pointed out several years ago,

in each interview Currin always passes through a tiny window of

clarity and says at least one thing that is true. In this

interview, this is it. We would be tempted to give him some

credit for humility or insight, except that we remember him

saying in those other interviews that he wanted to be famous and

to get lots of attention. In this one we are told he is right

where he wants to be, so it is difficult to work up much empathy

for him. We could take this quote as some sort of admission of

bad faith, but it makes more sense to take it like [the British

portrait painter] Stuart

Pearson Wright’s admission that the avant garde is right

about a lot of things. Especially as regards that first sentence:

the avant garde expects

figurative painters to be insecure, and Currin is good enough to

oblige them. They have spent half of every year’s budget for 80

years being sure that figurative painters were insecure, or

worse, and Currin would never have been allowed into the game if

he didn’t play along. Even if he weren’t

insecure, there is likely a clause in his contract that requires

him to say he is at

least five times a year.

Jed Perl at the New Republic has

been even harder on Currin than Currin pretends to be on himself.

He calls Currin’s paintings,

Mousy imitations of old master

portrait styles that would not earn him a freelance gig as a

magazine illustrator.

Strong, but too strong. This is

precisely where Currin should be, supposing he could find a

magazine that needed nearly nude cartoons in the snow. Currin has

an illustrator’s style as well as an illustrator’s mind and

level of creativity. He cannot give a face any real depth or

life, but he can certainly produce figures that are interesting

in their own limited ways. You wouldn’t want to look at Sno-bo

everyday: she would wear pretty thin, so to speak. But you don’t

mind looking once or twice. She’s cute and clever, and it would

be pointless to deny it. Is she a damn good illustration? Yes. Is

she worth a million dollars? No.

To show why I think this is

so, in even greater detail, let us look at what has been called

his best recent painting, by critics and non-critics alike. A

portrait of his son.

I agree that this is one of his

best works. It has a certain charm. It is not phony in any way.

It is the kind of straightforward painting we wish he were

allowed to do, and would do. But of course if he did this sort of

thing all the time, he wouldn’t be where he is. He would be

where I am.

And if he were where I am, then

people would have to look a bit harder at this work. Compared to

his other work, it is a gem. Compared to any good portrait, it is

a failure. Why? You may think it is due to some technical

problem. This is how the other portrait painters would critique

it; and the painting does have problems technically, as I will

show in a minute. But that is not why I think it fails. It fails

because the little boy is not alive. The eyes are dead. Remember

how Michael Kimmelman put it in his New York Times review

in 2003: “Eyes in Mr. Currin's work tend to be black holes,

sucking up light." Back then this was considered a bit of

flattery. The avant garde wants people looking like

mannequins, since this plays into their critique of society. But

Currin has not found it easy to turn off his “critical

distance” or his sangfroid or whatever it is. He has created no

connection here to his own son. The boy looks like a pretty doll.

Currin is finally beginning to

learn some of the technical tricks of the old masters, but he

still hasn’t learned the cardinal rule of traditional painting:

you have to make the face live. He should have studied Van

Dyck or Titian instead of Velasquez’ s Infantas. Velasquez

painted the princesses as little dolls, just like this, and that

is why no one likes them as much as his portraits of the dwarfs

or his other friends at court. Currin has an unerring instinct

for the lifeless and mannered, so that even when he goes to

Velasquez—the right teacher, in many ways—he still ends up

with an emotional nullity.

The eyes are the main problem,

since they have no life or sparkle. Part of this is strictly

technical. The eyeballs need to curve and the irises need touch

lights and color variation and so on. But it is more than that,

since the mouth also has no expression. You could add a lot of

technical tricks to liven up the paint of the mouth, but

it would still have no expression because Currin photographed the

boy when he was not expressing anything. The boy is very pretty,

and nattily dressed, but the mood of the piece is flat.

Currin also doesn’t know what he

is doing with his light. He doesn’t have enough tonal variation

in the skin to create a real curvature, and this is because he is

lighting from the wrong angle. He has only two basic tones in his

skin. He has no real highlights and no real shadows. This is what

flattens out the face and makes it look like an illustration.

Then look at what he does with the

background. He has chosen a good color, but he doesn’t appear

to know what to do when it meets the figure. He just takes it up

to the edge of the figure and lets it stop. It looks like a

pastel sketch or something. This is why the little boy looks

pasted onto the canvas. He doesn’t really live in that

background, it just hangs around him, flatly.

Currin has this problem with all

his edges here. It is because they didn’t teach him anything at

Yale and he is having to re-invent the wheel. He is scared to go

wet into wet, but you have to overlap and repaint to get these

edges to blend.

To be fair, he has also done a lot

of things right here. His color harmony is lovely. He hasn’t

felt a need to over-saturate, as so many realists now do. His

drawing is very good. The hair has a nice degree of finish, not

too much not too little. And he has picked a fetching costume.

All these things take real talent, and Currin is not without

talent. But because, up to now, he has been more interested in

getting rich and famous than in learning how to paint, he has

what he would be expected to have: a big bank account and an

unimpressive oeuvre.

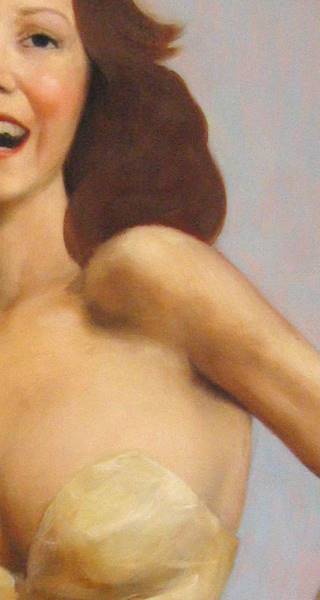

Just to put to rest all these

claims of mastery and direct comparisons to the greats, let's

look at a close-up of one of his better-known

paintings.

There

is nothing wrong with that as a piece of illustration, but don't

tell me it compares to Caravaggio or Sargent. Ignoring subject

matter and just looking at paint quality, anyone who has ever

held a brush will tell you Currin has only a tithe of the depth

or complexity of even the worst of the real painters of history.

Currin admits it himself, above. And this illustrative technique

was chosen on purpose. It is not a failing. If he really

achieved the complexity and depth of the Old Masters, he would be

thrown out of the avant garde as a dangerous virus. They can't

have that. They allow this mocking downgrade of realism in order

to undercut realism. Currin's technique is not an homage or a

return to mastery, it is intentional propaganda against

mastery. This is its use to the avant garde. Surely Currin

understands that.

Let’s return for a moment to Sno-bo.

Notice that I do Currin the favor of looking at his best work. It

is a work that is very popular and it is a work that I like.

Arthur Danto of The Nation says this of Hobo and

Sno-bo:

The two figures are exceedingly

mysterious. . . .As paintings they have the power to hold us in

front of them, contemplating meanings too fragile and remote for

application to life.

Come

on! “Exceedingly mysterious”? “Meanings too fragile and

remote”? I like the paintings, but I don’t see any mystery or

anything remote there. They’re clever cartoons, made specially

for guys who like their women skinny and blonde. I do, but I

can’t pretend there is anything mysterious about it,

particularly when I am looking at these cartoons. I thought that

was the whole point of them. Not to mystify, but to de-mystify.

Danto doesn’t even know how to look at an image, much less take

the artist at his word. If Currin had been trying consciously or

unconsciously to plumb some depths of sex or desire, do you think

he would have chosen this subject to paint, or given it such a

perfectly inane title? Currin is no doubt satisfied to allow such

misreadings, since they make the painting bigger and more

expensive than it is. But they remain egregious misreadings.

As another example of Danto’s

complete missing of every point, lets look at another quote:

One cannot become a Mannerist as a

matter of stylistic decision. One has to allow talents to show

that have been held in check all along.

Just the opposite of the truth, as

usual. If he would only ask Currin, I am sure Currin would tell

him that the mannerist style that he borrowed was borrowed as a

“stylistic decision,” with full premeditation. In fact, this

used to be the understanding about Currin’s style. It was good

precisely because it was premeditated, and therefore false. If it

had been genuine, if it had been arrived at in any natural way,

it would not have been accepted by the avant garde, by places

like the Whitney and the Guggenheim and MoMA. The Whitney has it

in writing somewhere, I think, that no earnestness in style will

be tolerated. If you are not a tongue-in-cheek realist, you are a

real realist, in which case you are a danger, a pariah, and a

potential terrorist.

In fact, Currin is on very

dangerous ground with this portrait of his son, and I think he

knows it. That is precisely why he was careful to surround it

with large canvases of porn and other ironic swagger in his show.

The avant garde may forgive him for one or two portraits of his

son, as a sample of aberrant behavior or a temporary sign of

madness. But he best not make a habit of it.

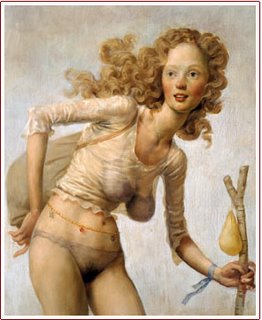

Odd Nerdrum is in precisely the

same boat, a boat floating three feet above the water—so that

no paddle may reach it. One of Nerdrum’s best-loved paintings

is the one of his daughter Amo.

The

child in this painting is fully alive, full of emotion, and

painted with complete technical knowledge and assurance. But

Nerdrum is in the same boat as Currin, since he cannot paint this

sort of thing everyday. It is allowed only once in a blue moon.

It must be surrounded by hooded freaks flexing their feet and

chanting at the moon. If Nerdrum painted all his subjects in a

straightforward manner, without manufactured mythologies and

premeditated weirdnesses, he would still be struggling in

obscurity, fenced out of the upper echelon of contemporary art

which is Pluralism. Amo wasn’t Nerdrum’s entrée into

the big time, it was paintings of one-armed hermaphrodites and

nudes dumping in the woods.

Let me simplify this for you even

more. Why is Currin in a higher price range? you may ask. 1)

Nerdrum is better technically: but that doesn’t matter, since

almost no one can see that. These major critics have compared

Currin to everyone from Parmigianino to Sargent, so it is clear

they are just dropping names. For them, any realist head is

pretty much equivalent to any other: the hierarchy from Alex Katz

to Titian is invisible to them, even as a sheer matter of

technique. 2) Currin and Nerdrum both paint weird things, so in

that regard we have a tie. In the avant garde, you are either in

or you are out, and they are weird enough to be in. The

hierarchies once you are in don’t have anything to do with the

actual art. You can have a brick on the floor or a 20-foot canvas

with six perfectly painted figures. The latter will not score you

any extra points, and it may actually harm you. But Currin and

Nerdrum are similar enough in the eyes of the avant garde that we

have no separation here. 3) The whole reason Nerdrum is not as

famous or expensive as Currin is that Nerdrum is in Iceland, not

New York City; he is not married to the daughter of a Jewish

dermatologist who he found in a faux gingerbread house in a

gallery in Soho; and he doesn’t go to parties with Mick Jagger

and Marc Jacobs and Chloe Sevigny, wearing two thousand dollar

suits. Nerdrum is still so naïve and un-American that he

actually spends his time painting. He should quit jacking off and

come sleep with Larry Gagosian or Mary Boone or someone.

As a closer, I want to look at one

more quote of Currin from this interview in the New Yorker:

The way things are painted trumps

everything else.

This is given us as a reward at the

very end of the article, as if it is very deep. But not only is

it not deep, it is not true. Ironically, it does push Currin in

line with Sargent, at least for a moment. Eleanor Heartney in Art

in America has claimed that Currin’s style has something in

common with Sargent’s style, but that is absurd. Currin has

nothing in common with Sargent but this quote. When Sargent was

at Broadway, Worchestershire, about the time he was painting

Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, he said something very much

like this. He said that it wasn’t so much what you painted as

how you painted it, and he attempted to prove it by setting up

his easel in a field at random and painting whatever was in front

of him. It didn’t last for long, of course, since that was all

balderdash. Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose is one of the most

manufactured things ever painted. It took months of model time

for the two girls, frozen in place every day at the same time, 15

minutes before sunset. This is how real paintings are made. They

aren’t accidents. And they aren’t paint samples, either. The

way things are painted doesn’t matter at all, unless they are

painted poorly. The subject and the treatment of the subject are

what matter.

There are dozens of perfectly good

and serviceable styles and methods in the history of figure

painting. Some are tight, some loose, some outlined, some

blended, some alla prima, some layered, some with high color,

some with little color. None of these methods is necessarily

superior to any other. As far as they are permanent, and express

what needed to be expressed, they are artistically equivalent.

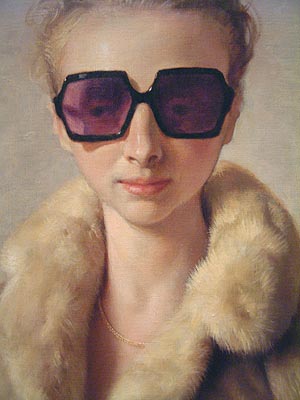

The perfect example of this is

Currin himself. Currin’s technique is not perfect, but Currin’s

main problem is not his technique. Currin’s main problem is his

subject matter. Most of the time he is piecing together weird

stuff he has found, in order to impress some critic or jury.

Except when he is painting his son, he is not painting anything

meaningful to him. Even his wife is used as a cut-out to be

pushed in some way. He is always using her to make some clever

statement or composition; he is never just painting her. I

haven’t seen a straightforward portrait of her, (although I

would like to). The closest he has come is Rachel in Fur.

But

she is wearing those stupid purple sunglasses. Even here he is

pushing his subject to appeal to modern standards and

requirements. It is as if he can’t turn off the self-conscious

games and asides for a moment. It isn’t enough for him—because

it isn’t enough for the avant garde—to just paint a face

because he loves it. Such a reason has no social relevance. What

can a critic say about a thing like that? What hook can a dealer

use to sell it?

If

this paper was useful to you in any way, please consider donating

a dollar (or more) to the SAVE THE ARTISTS FOUNDATION. This will

allow me to continue writing these "unpublishable"

things. Don't be confused by paying Melisa Smith--that is just

one of my many noms de plume. If you are a Paypal user,

there is no fee; so it might be worth your while to become one.

Otherwise they will rob us 33 cents for each transaction.

|